Abstract

Pseudocheiridae (Marsupialia: Diprotodontia) is a family of endemic Australasian arboreal folivores, more commonly known as ringtail possums. Seventeen extant species are grouped into six genera (Pseudocheirus, Pseudochirulus, Hemibelideus, Petauroides, Pseudochirops, Petropseudes). Pseudochirops and Pseudochirulus are the only genera with representatives on New Guinea and surrounding western islands. Here, we examine phylogenetic relationships among 13 of the 17 extant pseudocheirid species based on protein-coding portions of the ApoB, BRCA1, ENAM, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF genes. Maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian methods were used to estimate phylogenetic relationships. Two different relaxed molecular clock methods were used to estimate divergence times. Bayesian and maximum parsimony methods were used to reconstruct ancestral character states for geographic provenance and maximum elevation occupied. We find robust support for the monophyly of Pseudocheirinae (Pseudochirulus + Pseudocheirus), Hemibelidinae (Hemibelideus + Petauroides), and Pseudochiropsinae (Pseudochirops + Petropseudes), respectively, and for an association of Pseudocheirinae and Hemibelidinae to the exclusion of Pseudochiropsinae. Within Pseudochiropsinae, Petropseudes grouped more closely with the New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. than with the Australian Pseudochirops archeri, rendering Pseudochirops paraphyletic. New Guinean species belonging to Pseudochirops are monophyletic, as are New Guinean species belonging to Pseudochirulus. Molecular dates and ancestral reconstructions of geographic provenance combine to suggest that the ancestors of extant New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. and Pseudochirulus spp. dispersed from Australia to New Guinea ∼12.1–6.5 Ma (Pseudochirops) and ∼6.0–2.4 Ma (Pseudochirulus). Ancestral state reconstructions support the hypothesis that occupation of high elevations (>3000 m) is a derived feature that evolved on the terminal branch leading to Pseudochirops cupreus, and either evolved in the ancestor of Pseudochirulus forbesi, Pseudochirulus mayeri, and Pseudochirulus caroli, with subsequent loss in P. caroli, or evolved independently in P. mayeri and P. forbesi. Divergence times within the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade are generally coincident with the uplift of the central cordillera and other highlands. Diversification within New Guinean Pseudochirulus occurred in the Plio-Pleistocene after the establishment of the Central Range and other highlands.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10914-010-9129-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Marsupialia, New Guinea, Phylogenetic bracketing, Pseudocheiridae, Relaxed molecular clocks, Stratigraphic bounding

Introduction

The marsupial family Pseudocheiridae (Marsupialia: Diprotodontia) includes six extant genera (Pseudochirulus, Pseudocheirus, Pseudochirops, Petropseudes, Hemibelideus, Petauroides) and 16 to 17 (Nowak and Dickman 2005; Groves 2005) species commonly known as ringtail possums. With the exception of Petauroides, which has consistently been recognized as a genus, the other genera have variably been recognized as subgenera in Pseudocheirus (e.g., Tate 1945). Pseudocheirids inhabit mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and islands (Japen, Salawatti) to the west of New Guinea, and commonly occur in montane rainforests. Four of the five Pseudochirops species and five of the seven Pseudochirulus species are found only in New Guinea (Flannery 1995b; Fig. 1). Ringtail possums are arboreal folivores. Adaptations to arboreality include forcipate hands, in which the first two digits are at least partly opposable to the latter three, and a prehensile tail. Adaptations to folivory include selenodont molars and an enlarged cecum that acts as a fermentation chamber. In addition to extant pseudocheirid genera, extinct pseudocheirids have been referred to five genera: Paljara, Pildra, Marlu, Pseudokoala, and Gawinga (Woodburne et al. 1987; Bassarova and Archer 1999; Roberts et al. 2007, 2008, 2009). Paljara, Pildra, and Marlu are known from late Oligocene to early Miocene sediments in South Australia and Oligo-Miocene deposits of the Riversleigh World Heritage Area in Queensland (Woodburne et al. 1987; Bassarova and Archer 1999; Roberts et al. 2007). Pseudokoala is known from Plio-Pleistocene sediments in South Australia, Victoria, and Queensland (Turnbull and Lundelius 1970; Crosby et al. 2004). The fossil record of Gawinga is restricted to Riversleigh’s Faunal Zone B, which has been interpreted as early Miocene in age based on biocorrelation (Roberts et al. 2007).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of collecting localities for New Guinean pseudocheirids (Flannery 1995a, b) plotted on a generalized topographic map (modified from Flannery 1995b).

The most comprehensive phylogenetic studies of Pseudocheiridae are based on microcomplement fixation studies with albumin (Baverstock et al. 1990b), single-copy DNA-DNA hybridization data (Springer et al. 1992), craniodental characters (Springer 1993), and concatenated nuclear gene sequences (Meredith et al. 2009a). Baverstock et al. (1990b) treated all pseudocheirid species except for Petauroides volans as members of the genus Pseudocheirus, but their taxonomic sampling included representatives of all pseudocheirid genera as currently recognized by Groves (2005). Baverstock et al.’s (1990b) microcomplement fixation analyses provided support for three primary lineages: Pseudochirulus + Pseudocheirus, Hemibelideus + Petauroides, and Pseudochirops + Petropseudes (Baverstock et al. 1990b). Neither the New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. nor Pseudochirulus spp., respectively, were recovered as monophyletic (Baverstock et al. 1990b). DNA-DNA hybridization analyses included representatives of all pseudocheirid genera (sensu Groves 2005) excepting Petropseudes, and provided additional support for Pseudochirulus + Pseudocheirus, Hemibelideus + Petauroides, and Pseudochirops (Springer et al. 1992; Kirsch et al. 1997). Cladistic analyses of craniodental characters are generally in agreement with microcomplement fixation and DNA-DNA hybridization results and supported a sister group relationship between Petropseudes and representative species of Pseudochirops, a sister group relationship between Hemibelideus and Petauroides (Springer 1993), and an association of Pseudocheirus with Pseudochirulus (Springer 1993). None of the cladistic analyses of craniodental characters recovered the New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. as monophyletic (Springer 1993). Groves (2005), following Kirsch et al. (1997), divided Pseudocheiridae into the subfamilies Pseudochiropsinae (Pseudochirops), Hemibelidinae (Hemibelideus + Petauroides), and Pseudocheirinae (Pseudocheirus + Pseudochirulus + Petropseudes), although it should be noted that whereas Groves included Petropseudes in Pseudocheirinae, the taxonomic affinities of Petropseudes were not explicitly addressed in Kirsch et al.’s (1997) classification. Analyses based on concatenated nuclear DNA sequences (Meredith et al. 2009a) are in general agreement with microcomplement fixation (Baverstock et al. 1990a, b), DNA-DNA hybridization (Springer et al. 1992; Kirsch et al. 1997), and craniodental analyses (Springer 1993), and provide additional support for Hemibelideus + Petauroides, Pseudocheirus + Pseudochirulus, and Pseudochirops + Petropseudes. However, Pseudochirops was found to be paraphyletic with Petropseudes grouping more closely to Pseudochirops cupreus than to Pseudochirops archeri (Meredith et al. 2009a). As a result, Meredith et al. (2009a) suggested subsuming Petropseudes dahli into Pseudochirops as Pseudochirops (Petropseudes) dahli. Furthermore, Meredith et al. (2009a) found strong support for a basal split between the Pseudochirops + Petropseudes clade and all other extant pseudocheirids.

Hypotheses in historical biogeography are informed and underpinned by robust phylogenetic hypotheses, accurate estimates of divergence times, and reliable paleogeographic reconstructions. The present distribution of pseudocheirids, as well as other marsupial groups that currently inhabit Australia and New Guinea, have been explained through elements of both vicariance and dispersal. Flannery (1988) suggested a vicariant origin for the New Guinean mammal fauna, but a robust phylogenetic hypothesis for interrelationships among Australasian mammals was not available. Flannery (1988) synthesized the paleogeographic works of Dow (1977), Pieters et al. (1983), and Dow and Sukamoto (1984), and suggested a continuous connection between southern New Guinea and northern Australia from the late Paleocene into the Oligocene, which allowed for extensive faunal interchange. Flannery (1988) further suggested that the connection between Australia and New Guinea was severed in the early Miocene, although he allowed for the possibility of infrequent interchange between the Australian and New Guinean mammal faunas via waif dispersal subsequent to the vicariant sundering of Australia and New Guinea. Tropical rainforest pseudocheirids are “extremely poor dispersers” (Flannery 1995a) as a consequence of their largely or strictly arboreal lifestyle (Pahl et al. 1988; Laurance 1990; Laurance and Laurance 1999), and are therefore among the least probable candidates for waif dispersal. Australia and New Guinea remained isolated from each other until the Pleistocene (Dow 1977), when eustatic lowering of sea level allowed for interchange between the Australian and New Guinean mammal faunas (Flannery 1988).

If Flannery’s (1988) hypothesis is correct, we should expect to find two sets of divergences dates between Australian and New Guinean taxa: (1) divergence dates that predate the Miocene and reflect the vicariant separation of Australia and New Guinea, and (2) divergence dates from the latest Pliocene/Pleistocene that reflect resurgent land connections that developed at this time in conjunction with eustatic lowering of sea level. Flannery’s (1988) hypothesis was subsequently tested by Aplin et al. (1993) with microcomplement fixation data, and Kirsch and Springer (1993) with single-copy DNA hybridization data. Aplin et al. (1993) suggested a complex history of faunal interchanges between Australia and New Guinea in the Miocene (12–10 Ma) and Plio-Pleistocene (4.7–2.7 Ma) based on an albumin molecular clock and microcomplement fixation trees that contradicted the monophyly of New Guinean species of Pseudochirops and Pseudochirulus, respectively. Kirsch and Springer (1993) included a smaller number of taxa and suggested that representative Australian species belonging to Pseudochirops (P. archeri) and Pseudochirulus (P. herbertensis) separated from their New Guinean congeners (Pseudochirops cupreus and Pseudochirulus forbesi) 10.3 Ma and 10.9 Ma, respectively. Thus, the molecular studies of both Aplin et al. (1993) and Kirsch and Springer (1993) suggest the possibility of land bridges between Australia and New Guinea during the Miocene (Aplin et al. 1993; Kirsch and Springer 1993), or that marsupials are better dispersers than has previously been thought (Kirsch and Springer 1993). In support of possible land connections in the late Tertiary, Aplin et al. (1993) cited Pigram et al. (1989) and Davies (1990). Pigram et al. (1989) found that carbonate sedimentation on the Papuan platform was progressively replaced by more clastic deposition during the late Tertiary, and that clastic deposition terminated with widespread paralic sedimentation in the Pliocene. Davies (1990) found Miocene paraconformities in the stratigraphy of the Papuan platform that “could well represent depositional hiatuses” (Aplin et al. 1993: 142). These paraconformities date to 9 Ma and 4.5 Ma, and are in the range of Aplin et al.’s (1993) estimated dates for marsupial dispersal events. The main difficulty with previous molecular studies that have reconstructed the historical biogeography of pseudocheirids is that they have not been underpinned by a robust phylogeny that includes extensive taxonomic sampling.

The evolutionary history of the New Guinean mammal fauna has been impacted not only by vicariance/dispersal events, but also by tectonic forces that have shaped New Guinea’s physiography. New Guinea is a type locality of island arc-continent collision that occurred during the Cenozoic (van Ufford and Cloos 2005). The geological history of New Guinea is complex, and the number and timing of Cenozoic tectonic events has been debated (van Ufford and Cloos 2005). Tectonic models of New Guinea range from one discrete collisional event to prolonged and piecemeal accretion involving at least 32 distinct tectonostratigraphic terranes (reviewed in van Ufford and Cloos 2005). The most recent synthesis of available geological data (Cloos et al. 2005; van Ufford and Cloos 2005) suggests that the Cenozoic tectonic history of New Guinea involved two distinct orogenic events. The first event, the Peninsular orogeny of Oligocene age (∼35–30 Ma), was restricted to the Papuan Peninsula in easternmost New Guinea and created the Peninsular Range. The second event, the Central Range orogeny, commenced in the latest middle Miocene and resulted in the mountainous spine of New Guinea that extends from the Bird’s Neck region to the Papuan Peninsula (van Ufford and Cloos 2005). By about 5 million years ago, the central cordillera in western New Guinea included topography that was between 3000 and 5000 m high. New Guinea has distinct zoogeographic provinces, which roughly correspond to its geological provinces (Flannery 1995b). Within these zoogeographic provinces, species belonging to Pseudochirops and Pseudochirulus both show altitudinal zonation (Table 1; Fig. 1) that has been shaped by climate and possibly species competition (Flannery 1995b). Up to four pseudocheirid species, each in a distinct weight class and with unique nesting habits, are known to exist sympatrically in New Guinea (Flannery 1995b; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Geographic range, habitat, diet, and altitudinal for Australian and New Guinean pseudocheirids included in this study (data from Tate 1945; Thomson and Owen 1964; Flannery 1995b; Meynecke 2004; Helgen 2007a, b)

| Geographic Range | Habitat | Diet | Altitude (meters) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudocheirus peregrinus | Parts of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania | Scrub, sclerophyll forest, rainforest | Mostly leaves, but also flowers and fruits (dietary preferences vary geographically) | Sea level—1500 |

| Pseudochirulus herbertensis | Queensland (between Ingham and Cairns) | Tropical rainforest; occasionally tall open forests of Flooded Gum that fringe rainforests | Mostly leaves | >350 m |

| Pseudochirulus canescens | Widespread throughout lowland New Guinea | Lowland forests | Mosses, ferns, lichens, leaves | Sea level—1700 |

| Pseudochirulus caroli | Irian Jaya (Weyland Range, Noord River basin, Baliem Valley, Maokop Range) | Noord River basin, Weyland Range, Baliem Valley, | No information | 0-2200 |

| Pseudochirulus mayeri | New Guinean central cordillera | Moss forests | Leaves, mosses, ferns, lichens, fungus, and pollen | 1200–4200 (most abundant > 2000) |

| Pseudochirulus forbesi | Eastern half of the New Guinean central cordillera, Vogelkop Peninsula North Coast Ranges, Huon Peninsula | Montane forests | Primalily leaves, includes those of Medinella | 450–3800 |

| Hemibelideus lemuroides | Queensland (between Ingham and Cairns, Mount Carbine Tableland) | Tropical rainforest | Mostly leaves; also certain flowers and the outer covering of the yellow walnut | >450 |

| Petauroides volans | Eastern Australia (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria) | Sclerophyll forest | Almost exclusively eucalypt leaves | |

| Petropseudes dahli | Western Australia (northeastern Kimberley region), Northern Territory (Katherine and Roper Rivers region, Groote Eylandt), Queensland (northwestern region) | Rocky outcrops | Flowers, fruits, leaves | <1000 |

| Pseudochirops archeri | Queensland (between Paluma and the Mount Windsor Tableland, west of Mossman) | Tropical rainforest | Almost exclusively leaves, mainly from several species of fig | 300–1200 |

| Pseudochirops corinnae | Huon Peninsula, New Guinean central cordillera | Lower montane rainforest | Primarily leaves | 900–2900 (most common at 1800–2200) |

| Pseudochirops cupreus | New Guinean central cordillera; Wissel Lakes Region | Rainforest; scrub and herbfield at 3700 m in Prinz Wilhelm V Range in Irian Jaya | Primarily leaves | 1350–4000 (most common above 2500) |

| Pseudochirops albertisii | New Guinea (Arfak Mountains, Weyland Range, North Coast Ranges), Japen Island | Lower montane rainforest | Known stomach contents include leaves, fruits, and buds of Ficus sp. | 300–2500 |

In this paper, we use a nuclear protein-coding DNA data set to infer a phylogeny and timescale for 13 extant pseudocheirids. We also perform relaxed clock analyses and ancestral state reconstructions for geographic provenance to determine the number and timing of dispersal events to New Guinea within the Pseudochirulus and Pseudochirops clades. Finally, we combine phylogeny, divergence times, reconstructions of geographic provenance and maximum elevation occupied, and recent information on the geological history of New Guinea to evaluate whether or not pseudocheirid species diversified in synchrony with the uplift of the New Guinean cordillera and highlands or filled in habitats with pre-existing altitudinal differentiation.

Materials and methods

Taxon sampling

We included 13 of 17 recognized pseudocheirid species (Groves 2005) and nine marsupial outgroups with representatives from all other petauroid families (Acrobatidae, Petauridae, Tarsipedidae). Previous molecular studies provide robust support for petauroid monophyly (Springer and Kirsch 1991; Kirsch et al. 1997; Kavanagh et al. 2004; Phillips and Pratt 2008; Meredith et al. 2009a; Springer et al. 2009). Taxon sampling and GenBank accession numbers are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

GenBank accession numbers and taxonomy followed in this study. New sequences are indicated with asterisks

Gene sampling

Genomic DNA was extracted following Meredith et al. (2009a). Portions of protein coding regions of six nuclear genes that were used in this study were chosen based on their utility in previous mammalian phylogenetic studies (Amrine-Madsen et al. 2003; Meredith et al. 2008a, b, c; Meredith et al. 2009a, b, c). ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF were amplified, cleaned, and sequenced following the protocols outlined in Meredith et al. (2009a). Approximately 900 bp of the 5’ end of exon 10 of the enamelin gene (ENAM) were amplified, cleaned, and sequenced following the protocols outlined in Meredith et al. (2009b).

Alignments

We identified alignment ambiguous regions using SOAP v1.2a4 (Löytynoja and Milinkovitch 2001) with gap opening (11–19) and gap extension (3–11) penalties in steps of two (25 total alignments). Prior to the removal of the alignment ambiguous regions, the resultant alignment was manually re-aligned with Se-Al (Rambaut 1996) to keep gaps in synchrony with codons. We removed entire codon positions from the alignment in cases where partial codons were included in the ambiguous region. Twenty-one base pairs were identified and removed from the BRCA1 alignment. The remaining 6928 sites were retained for subsequent analyses (ApoB = 760 sites; BRCA1 = 2477 sites; ENAM = 900 sites; IRBP = 1276 sites; Rag1 = 544 sites; vWF = 971 sites). The aligned nexus file is given in Supplementary Information.

Data compatibility

Bootstrap compatibility tests (de Queiroz 1993; Teeling et al. 2002) were performed with RAxML 7.0.4 (Stamatakis 2006) to assess the appropriateness of combining individual gene segments into a concatenated data set. Bootstrap analyses for each gene segment included 500 bootstrap replicates, and either the GTR + Γ (ApoB, BRCA1, ENAM) or GTR + I + Γ (IRBP, Rag1, vWF) model of sequence evolution (see Phylogenetic analyses). All bootstrap analyses were started from randomized MP starting trees, employed the fast hill-climbing algorithm, and estimated free model parameters. No conflicting nodes were found at or above the 90% bootstrap support level. PAUP 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002) was used to implement the partition homogeneity test (Farris et al. 1994) with six partitions corresponding to each of the gene segments, 1000 replicates, and ten taxon input orders per replicate. The results of the partition homogeneity test were significant (p = 0.003). However, Cunningham (1997), Barker and Lutzoni (2002), and Darlu and Lecointre (2002) suggested that a significance threshold of 0.05 might be too conservative for the partition homogeneity test; Cunningham (1997) suggested using a critical alpha value between 0.01 and 0.001. In contrast to Cunningham (1997) and others, Dowton and Austin (2002) showed that the partition homogeneity test sometimes results in estimates of congruence that are too high. Given the conflicting results reported above for the bootstrap compatibility and partition homogeneity tests, and the uncertainty associated with interpreting the results of partition homogeneity tests, we chose to combine the six individual gene segments into a single concatenation based on the results of bootstrap compatibility tests.

Phylogenetic analyses

Maximum likelihood (ML), Bayesian, and maximum parsimony (MP) analyses were performed with RAxML (7.0.4) (Stamatakis 2006), MrBayes v3.1.1 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003), and PAUP 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002), respectively. Gaps were treated as missing data in all analyses. ML bootstrap analyses employed 500 replicates. MP bootstrap analyses implemented 1000 replicates, 10 randomized taxon input orders per replicate, and tree-bisection and reconnection branch swapping.

For the ML and Bayesian analyses we performed partitioned analyses, which allowed each gene to have its own parameters, and non-partitioned analyses, which treated the concatenation as a single gene. In addition, we performed a ML analysis on each gene segment. Best-fit models of molecular evolution were chosen using the Akaike Information Criterion as implemented in Modeltest 3.06 (Posada and Crandall 1998). Models chosen were GTR + Γ (ApoB); TVM + Γ (BRCA1); HKY + Γ (ENAM); TVM + I + Γ (IRBP); TIM + I + Γ (Rag1); TrNef + I + Γ (vWF); GTR + I + Γ (concatenation). If the model of sequence evolution suggested by Modeltest was not available in MrBayes, we used the next most general model. RAxML only implements the GTR substitution matrix, and the results of Modeltest were only used to inform the possible inclusion of a rate-heterogeneity parameter (Γ or Γ + I). ML analyses were started from randomized MP starting trees, employed the fast hill-climbing algorithm, and estimated free model parameters. Bayesian analyses used default settings for priors, random starting trees, eight Markov chains (seven hot and one cold) sampled every 1000 generations, and were terminated once the average standard deviation of the split frequencies for the simultaneous analyses fell below 0.01 (at least 5 million generations).

Molecular dating analyses

The likelihood ratio statistic rejected the molecular clock hypothesis for each of the six genes and the concatenation (P < 0.001). We therefore employed two relaxed clock Bayesian methods, BEAST v1.4.8 (Drummond et al. 2006; Drummond and Rambaut 2007) and Multidivtime (version 9-25-03; Kishino et al. 2001; Thorne and Kishino 2002), to estimate posterior probabilities of divergence times. BEAST v1.4.8 allows for the incorporation of multiple constraints from the fossil record, simultaneously estimates both the phylogeny and divergence times, allows for complex models of molecular evolution, does not assume that rates among lineages are correlated, and permits both “soft” and “hard” bounded constraints (Hedges and Kumar 2004; Yang and Rannala 2006). In contrast, Multidivtime requires a rooted tree topology, only allows for fixed minimum and maximum constraints, and assumes autocorrelated rates of molecular evolution among lineages (Thorne et al. 1998; Kishino et al. 2001; Thorne and Kishino 2002).

The data set was treated both as non-partitioned (one model of sequence evolution for all genes) and partitioned (individual models of sequence evolution for each gene). Modeltest (Posada and Crandall 1998) was used to guide model selection for BEAST analyses, with the caveat that BEAST only implements two substitution models [HKY (two rates); GTR (six rates)], with or without a gamma distribution of rates and an allowance for a proportion of invariant sites. If Modeltest suggested more than two substitution rates, but fewer than six substitution rates, we used the more general GTR model.

Analyses with BEAST v1.4.8 implemented the uncorrelated lognormal distribution (UCLN) model, which draws the rate of each lineage independently from a lognormal distribution, with a Yule tree prior. For both the non-partitioned and partitioned data sets, BEAST analyses were run for 30 million generation with sampling every 1000 generations and a burnin of three million generations. Tracer v1.4.1 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007) was used to inspect stationarity/mixing and to verify that the estimated sample size was greater than 200 for all parameters. In soft-bounded analyses, prior probabilities for fossil-calibrated nodes followed a normal distribution, with 95% of the distribution between the specified minima and maxima and 2.5% in each tail. We also performed hard-bounded analyses that employed uniform priors with fixed minima and maxima on the calibrated nodes. The monophyly of the ingroup (Tarsipedidae + Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae) was constrained, but monophyly was not constrained for any other nodes.

For the Multidivtime analyses, we used the topology shown in Figs. 2 and 3 with Acrobatidae as the outgroup. We employed the F84 + Γ model of sequence evolution (Swofford et al. 1996) which is the most complicated model implemented by Multidivtime. Among-site rate heterogeneity was approximated with four discrete categories for the Γ distribution, which along with the transition/transversion parameter were estimated with Paup 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002). Branch lengths were estimated with estbranches. We used 38.2 million years as the mean age of the prior distribution for the base of Tarsipedidae + Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae based on a previous molecular estimate for the age of this clade (Meredith et al. 2009a). We set the mean prior for the rate of molecular evolution at the ingroup root node equal to the median amount of evolution from the ingroup root node to the ingroup tips divided by the mean age of the prior distribution for the root of Tarsipedidae + Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae. All analyses were run for one million generations with chain sampling every 100 generations and a burnin of 100,000 generations.

Fig. 2.

Bayesian tree obtained from the gene partitioned Bayesian analysis. Values above and below branches correspond to the mean Bayesian posterior probabilities (expressed as percentages) based on the two simultaneous runs, and ML bootstrap support percentages for the RAxML gene-partitioned analysis, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogram obtained from the RAxML gene partitioned analysis (GTR + I + Γ model of sequence evolution) using protein-coding portions of ApoB, BRCA1, ENAM, IRBP, Rag1, and vWF.

Fossil constraints

We used minimum and maximum age constraints for nine different nodes (Fig. 4). Node numbers in Fig. 4 correspond to labeled nodes on the chronogram in Fig. 5. For the Multidivtime analyses, the minimum and maximum constraints for nodes 1 and 9 were not available because the outgroup (Acrobatidae) was trimmed from the tree by estbranches prior to running Multidivtime. Woodburne et al. (1993), Myers and Archer (1997), Gradstein et al. (2004), Archer et al. (2006), and Travouillon et al. (2006) were used for biocorrelation and geologic dates of Australasian deposits. The age of Riversleigh Faunal Zone A is based on Myers and Archer’s (1997) correlation of this unit to the Ngama Local Fauna, which Woodburne et al. (1993) dated at 25.0–24.7 Ma. The ages of Riversleigh Faunal Zones B (23.03–15.97 Ma) and C (15.97–11.61 Ma) are based on correlations with Gradstein et al.’s (2004) timescale. Fossils from Mt. Etna were given ages in millions of years based on their presumed epoch (e.g. middle Pleistocene ∼0.5 Ma; Hocknull et al. 2007). Minimum ages were assigned based on the age of the oldest unequivocal fossil belonging to a given clade (Fig. 4). Maximum ages were assigned based on the maximum of stratigraphic bounding (Benton and Donoghue 2007), phylogenetic bracketing (Reisz and Müller 2004; Müller and Reisz 2005), and phylogenetic uncertainty. Stratigraphic bounding uses the age of underlying fossil-bearing deposits that lack fossils for a given clade to establish a maximum age; phylogenetic bracketing uses the age of the oldest fossils for the next node below a divergence event to establish a maximum age; and phylogenetic uncertainty allows that the age of a clade may be as old as described fossils of uncertain phylogenetic affinity that may or may not belong to a clade. Hedges et al. (2006: 770) correctly point out a limitation of the phylogenetic bracketing approach, i.e., that the oldest fossil of the most closely related group is “only a minimum for its own lineage and the true maximum—and splitting event—could be much older.” Viewed another way, the fossil of the most closely related group establishes a minimum for the maximum. The maximum may turn out to be older based on other criteria such as stratigraphic bounding and/or phylogenetic uncertainty. Given the sketchy record of Australasian mammal fossils, we followed Meredith et al.’s (2008b) recommendations and did not restrict stratigraphic bounding and phylogenetic bracketing to the immediately underlying fossil-bearing deposit or the sister group (= 1st outgroup), respectively. Rather, the maximum age based on stratigraphic bounding encompassed two successive underlying fossil-bearing deposits that did not contain any fossils from the lineage of interest. Similarly, phylogenetic bracketing encompassed the age of the oldest fossils that were up to two nodes below the divergence event (i.e., the oldest fossils belonging to either the1st or 2nd outgroup) to establish a maximum age (see Fig. 4; Table 3). All fossils that were incorporated into our compendium of minimum and maximum constraints were personally examined by us (K.K.R.) or were obtained from fully described/figured specimens in refereed articles. In cases where the oldest fossil was from a late Oligocene site, we used the age of the Tingamarra Local Fauna near Murgon (54.6 ± 0.05 Ma; Godthelp et al. 1992; Beck et al. 2008), as this is the only marsupial-bearing deposit in Australasia that pre-dates the late Oligocene.

Node 1 (Acrobatidae): The oldest described/figured acrobatids (Acrobates sp.) come from Mount Etna deposits in Queensland (∼0.50–0.28 Ma; Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007). Putative acrobatids have been reported from Riversleigh (23.03–15.97 Ma; Archer et al. 1999), but these fossils have not been formally described/figured and were not reported in Archer et al. (2006). As a result, the Riversleigh acrobatids were not used as fossil constraints in our analyses. The oldest described tarsipedid, pseudocheirid, or petaurid, which together comprise the 1st outgroup, are the pseudocheirids Paljara sp. A from Zone A of the Etadunna Formation (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993), and Pildra antiquus from the Pinpa Local Fauna of the Namba Formation, which has been biocorrelated with Zone A of the Etadunna Formation (Woodburne et al. 1987, 1993). We used a minimum of 0.28 Ma and a maximum of 25.7 Ma (phylogenetic bracketing) for node 1.

Node 2 (Petauridae): Fossils belonging to Petaurus sp. have been described from a Pliocene Hamilton Local Fauna (4.46 ± 0.1 Ma; Turnbull et al. 2003) in Victoria. Turnbull et al. (2003: 534) note that the Hamilton Petaurus fossils include individual specimens that are near living P. norfolcensis, P. breviceps, and P. australis, but also allow for the possibility that all of the Hamilton Petaurus specimens belong to “one highly variable species.” Fossils of Dactylopsila spp. have been described from Queensland (Mount Etna; ∼0.5–0.28 Ma; Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007). Fossils belonging to Dactylopsila sp. have also been reported from Riversleigh (15.97–11.61 Ma, Archer et al. 1999), but these fossils have yet to be described/figured and were not reported in Archer et al. (2006). As a result, the Riversleigh Dactylopsila sp. was not used as a fossil constraint in our analyses and we used a minimum of 4.36 Ma for node 2. Paljara sp. A and Pildra antiquus are the oldest representatives of the first outgroup, Pseudocheiridae (see node 1), and establish a maximum of 25.7 Ma (phylogenetic bracketing) for node 2.

Node 3 (Pseudocheiridae): The oldest described crown pseudocheirids are from the Hamilton Local Fauna (4.46 Ma; Turnbull et al. 2003; see nodes 5–6) and Pliocene Bluff Downs Local Fauna (3.6 Ma; Mackness et al. 2000; Mackness and Archer 2001; see node 5). We used a minimum of 4.36 Ma for node 3. The oldest stem pseudocheirids (1st outgroup) are Paljara sp. A and Pildra antiquus (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993). We used a maximum of 25.7 Ma (phylogenetic bracketing) for node 3.

Node 4 (Petropseudes + Pseudochirops): Two Pseudochirops spp. have been reported from Riversleigh Faunal Zone C deposits (15.97–11.61 Ma; Archer et al. 2006). These species have since been identified as belonging to an extinct, undescribed genus (Roberts et al. unpublished). Pseudochirops winteri from the Pliocene Bluff Downs Local Fauna (3.62 ± 0.5 Ma; Mackness et al. 2000; Mackness and Archer 2001) is the oldest described member of Pseudochirops. Petropseudes dahli has been reported from Riversleigh Pliocene Rackham’s Roost Site (5.3–2.6 Ma; Archer et al. 1997). The fossil has yet to be described or figured, but is included in Archer et al. (2006) and is the only fossil record for Petropseudes. One of us (K.K.R.) has examined the putative Petropseudes specimen and considers that whereas it could belong to Petropseudes, there is insufficient material to confirm this identification. The specimen should therefore be considered Pseudocheiridae gen. et sp. indet., and the presence of Petropseudes cannot be assumed for the Pliocene. The oldest described fossils of Pseudocheirinae or Hemibelidinae, which together comprise the 1st outgroup, are from the Hamilton Local Fauna (4.46 ± 0.1 Ma; Turnbull et al. 2003). The oldest described stem pseudocheirids (2nd outgroup) are Paljara sp. A and Pildra antiquus (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993). We used a minimum of 3.12 Ma and a maximum of 25.7 Ma (phylogenetic bracketing) for node 4.

Node 5 (Hemibelideus + Petauroides): Petauroides spp. (Mount Etna; ∼0.5–0.28 Ma; Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007) and Petauroides stirtoni (Hamilton Local Fauna; 4.46 ± 0.1 Ma; Turnbull et al. 2003) are the oldest described species of either Hemibelideus or Petauroides. We used a minimum of 4.36 Ma for node 5. All of the described fossils belonging to the 1st outgroup (Pseudocheirinae) and 2nd outgroup (Pseudochirops + Petropseudes) are ≤4.46 Ma, so we used a maximum of 15.97 Ma for node 5 based on stratigraphic bounding (Fig. 4).

Node 6 (Pseudochirulus + Pseudocheirus): Pseudochirulus sp. 1 (Mount Etna; ∼0.5–0.28 Ma; Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007), Pseudocheirus marshalli (Hamilton Local Fauna; 4.46 ± 0.1 Ma; Turnbull et al. 2003), and Pseudocheirus spp. (Mount Etna; ∼0.5–0.28 Ma; Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007) are the oldest described species belonging to Pseudochirulus or Pseudocheirus. We used a minimum of 4.36 Ma for node 6. All of the described fossils belonging to the 1st outgroup (Hemibelidinae) and 2nd outgroup (Pseudochirops + Petropseudes) are ≤4.46 Ma, so we used a maximum of 15.97 Ma for node 6 based on stratigraphic bounding (Fig. 4).

Node 7 (Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae): The oldest described fossils belonging to Petauridae or Pseudocheiridae are Paljara sp. A and Pildra antiquus (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993; see node 3). Extinct pilkipildrids are sometimes included in an unresolved crown-clade with petaurids and pseudocheirids (Crosby et al. 2004), but the fossil record of pilkipildrids only extends as far back as the fossil record of pseudocheirids. The oldest fossils belonging to Tarsipedidae (1st outgroup) and Acrobatidae (2nd outgroup) are much younger than the oldest pseudocheirids. No petauroids are known from the Tingamarra Local Fauna near Murgon (54.6 ± 0.05 Ma; Godthelp et al. 1992; Beck et al. 2008). We used a minimum of 25.5 Ma and a maximum of 54.65 Ma (stratigraphic bounding) for node 7.

Node 8 (Tarsipedidae + Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae): The earliest fossils belonging to Tarsipedidae are late Pleistocene in age (Long et al. 2002). The oldest fossils belonging to Petauridae or Pseudocheiridae and Paljara sp. A and Pildra antiquus (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1987, 1993). The oldest fossils belonging to Acrobatidae (1st outgroup) or Australoplagiaulacoida (2nd outgroup) are stem kangaroos from Zone A of the Etadunna Formation (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993). We used a minimum of 25.5 Ma and a maximum of 54.65 Ma (stratigraphic bounding) for node 8.

Node 9 (Petauroidea): The oldest marsupial bearing deposits in Australia are known from the Tingamarra Local Fauna (54.6 ± 0.05 Ma; Queensland; Godthelp et al. 1992; Beck et al. 2008) and as of yet no petauroids have been identified. Fossil pseudocheirids from Oligo-Miocene deposits are the oldest described members of the Petauroidea (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1987, 1993). The oldest fossils belonging to Australoplagiaulacoida (1st outgroup) or Vombatiformes (2nd outgroup) are stem kangaroos and stem koalas, respectively, from Zone A of the Etadunna Formation (25.7–25.5 Ma; Woodburne et al. 1993). We used a minimum of 25.5 Ma and a maximum of 54.65 Ma (stratigraphic bounding) for node 9.

Fig. 4.

Visual representation of the methodology used to determine fossil constraints employed in this study. Fossil/Faunal zones used to determine the oldest representative of a given lineage are given in Table 3. Ages of epoch boundaries are based on Gradstein et al. (2004). Plio. = Pliocene; Pl. = Pleistocene.

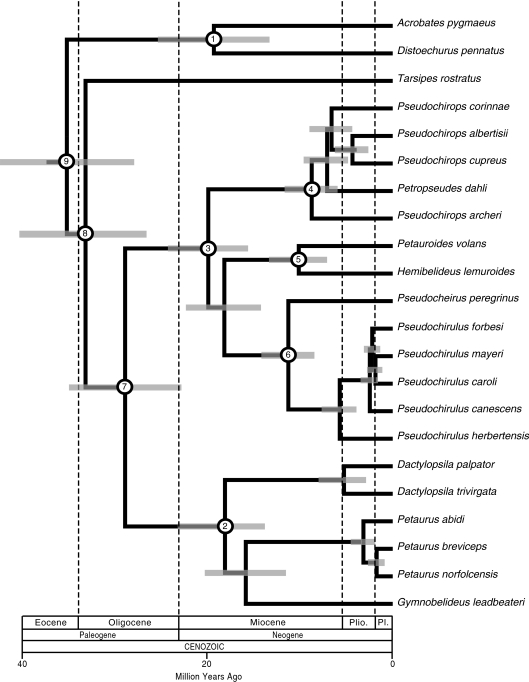

Fig. 5.

Timeline in millions of years before present for pseudocheirid evolution based on the BEAST partitioned analysis. Grey bars indicate 95% highest posterior densities. Numbers within open circled nodes indicate calibrated nodes. Plio. = Pliocene; Pl. = Pleistocene.

Table 3.

Fossil localities that were utilized in determining minimum and maximum fossil constraints

| Fossil/Faunal Zone Locality | Reference(s) |

|---|---|

| Pleistocene | |

| Cave Sites (late Pleistocene) | Long et al. 2002 |

| Mt. Etna deposits (∼0.28–0.50 Ma) | Hocknull 2005; Hocknull et al. 2007 |

| Late Pliocene to early Pleistocene | |

| Childer’s Cove (∼1.81–2.59 Ma) | Piper et al. 2006 |

| Dog Rocks Local Fauna (∼1.81–2.59 Ma) | Piper et al. 2006 |

| Awe Local Fauna New Guinea (2.59–3.60 Ma) | Rich 1991 |

| Chinchilla Sands (3.4 Ma) | Rich 1991; Tedford et al. 1992 |

| Curramulka Local Fauna (3.6 Ma) | Pledge 1992 |

| Bow Local Fauna (3.62 Ma) | Rich 1991 |

| Kanunka Local Fauna (3.4 Ma) | Tedford et al. 2006 |

| Bluff Downs Local Fauna (3.62 Ma) | Rich 1991; Mackness et al. 2000; Mackness and Archer 2001 |

| Rackham Roost Site (∼2.6–5.3 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Coimadai Local Fauna (3.60–5.33 Ma) | Piper et al. 2006 |

| Hamilton Local Fauna (4.46 ± 0.1 Ma) | Turnbull et al. 2003; Tedford et al. 2006 |

| Riversleigh Two Trees Site (∼2.6–5.3 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Late Miocene | |

| Alcoota/Ongeva Local Fauna (∼7–8 Ma) | Megirian et al. 1996; Murray and Megirian 1992 |

| Riversleigh Encore Local Fauna (∼10 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Bullock Creek Local Fauna (∼12 Ma) | Murray and Megirian 1992 |

| Middle Miocene | |

| Riversleigh Faunal Zone C (11.61–15.97 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Early Miocene | |

| Riversleigh Faunal Zone B (15.97–23.03 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Late Oligocene | |

| Geilston Bay Deposits (23 ± 0.5 Ma) | Tedford and Kemp 1998 |

| Kangaroo Well Local Fauna (∼23.03 Ma) | Megirian et al. 2004 |

| Etadunna Formation (24.2–∼25.7 Ma) | Woodburne et al. 1993 |

| Namba Fm (∼equivalent to Etadunna Fm) | Rich 1991; Woodburne et al. 1993 |

| Riversleigh Faunal Zone A (24.7–25.0 Ma) | Archer et al. 2006 |

| Early Eocene | |

| Tingamarra Local Fauna (54.6 ± 0.05 Ma) | Godthelp et al. 1992 |

Ancestral state reconstructions

SIMMAP (version 1.0 B2.3.2; Bollback 2006) and MacClade 4.08 (Maddison and Maddison 2005) were used to estimate ancestral states for geographic provenance of origin for Pseudocheiridae [0: Australia and Tasmania; 1: New Guinea and surrounding islands], and maximum elevation [0: ≤ 1500 m; 1: between 1500 and 3000 m; and 2: ≥ 3000 m (ordered character)]. MacClade uses parsimony to infer the minimal number of steps needed to explain the distribution of characters found in the terminal branches. SIMMAP implements the methods of Nielsen (2002) and Huelsenbeck et al. (2003) for stochastically mapping discrete mutations onto phylogenies. SIMMAP uses a Bayesian approach to calculate a posterior probability distribution that accommodates uncertainty in ancestral states, evolutionary rates, and the phylogeny. The rate prior is described by the parameters α and β, which specify the mean (α/β) and variance (α/β2). We used 50 discrete categories to approximate the gamma distribution and rescaled branch lengths before applying the prior to maintain branch length proportionality. We used three sets of morphological priors (α = 1 and β = 1; α = 3 and β = 2; α = 5 and β = 5) to investigate the robustness of our estimates. An additional parameter, the bias parameter, is required for analyses with binary characters. The bias parameter prior was specified with α = 1, which specifies an uninformative prior with equal prior probabilities. We used all post burn-in trees from one run of the partitioned Bayesian analysis (12212 trees) with ten draws from the prior distribution; acrobatids, Tarsipes, and petaurids were excluded from the SIMMAP analyses, but the pseudocheirid trees remained rooted. The three different combinations of priors gave posterior probabilities that differed by no more than 0.1199 (ancestral areas) or 0.1007 (elevation) at a given node, and we only report the results for analyses with α = 3 and β = 2.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

Concatenation

The maximum posterior probability tree based on the partitioned analysis is shown in Fig. 2, which also shows Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) and bootstrap support percentages for the partitioned analyses. The ML tree is shown in Fig. 3. Bayesian posterior probabilities, along with ML and MP bootstrap support percentages, are summarized in Table 4 for nodes that were not supported at the 100% bootstrap and 1.00 posterior probability levels.

Table 4.

Posterior probabilities and bootstrap support percentages. All clades that were supported at the 100% bootstrap and 1.00 posterior probability levels are not shown. Posterior probabilities are given as the average of the two independent runs. Partitioned = each gene was modeled to have its own model of molecular evolution; Non-partitioned = ApoB, BRCA1, IRBP, Rag1, vWF, ENAM were treated as a single gene; MP = maximum parsimony; ML = maximum likelihood

| Phylogenetic Hypothesis | MP | ML | Bayesian Analyses | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAxML | |||||

| Partitioned | Non-Partitioned | Partitioned | Non-Partitioned | ||

| Gymnobelideus + Petaurus | 88 | 98 | 96 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Petaurus breviceps + Petaurus norfolcensis | 65 | 75 | 65 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| Pseudochirulus forbesi + P. mayeri + P. caroli | 79 | 75 | 81 | 0.75 | 0.84 |

| Pseudochirulus mayeri + P. caroli | 77 | 75 | 80 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Pseudochirops monophyly (excluding Petropseudes) | 0.3 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Petropseudes + New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. | 92 | 94 | 95 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Pseudochirops corinnae + P. cupreus + P. albertisii | 42 | 73 | 66 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Hemibelidinae + Pseudocheirinae | 99 | 99 | 99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

All analyses recovered Acrobatidae, Petauridae, and Pseudocheiridae as monophyletic families. Within Petauridae, Gymnobelideus and Petaurus grouped to the exclusion of Dactylopsila. Within Petaurus, P. breviceps and P. norfolcensis grouped to the exclusion of P. abidi.

Three groups within Pseudocheiridae were recovered in all analyses: Hemibelidinae (Petauroides + Hemibelideus); a modified Pseudocheirinae (Pseudocheirus + Pseudochirulus) that does not include Petropseudes; and a modified Pseudochiropsinae that includes Pseudochirops and Petropseudes. In all analyses, Hemibelidinae grouped with Pseudocheirinae. Within Pseudochiropsinae, the basal split was between Pseudochirops archeri (Australia) and a clade containing Petropseudes dahli (Australia) and New Guinean species of Pseudochirops. Within the latter clade, Pseudochirops albertisii and P. cupreus were sister taxa, P. corinnae was sister to these two, and Petropseudes dahli was sister to these three. Within Pseudocheirinae, Pseudocheirus and Pseudochirulus were recovered as sister taxa. Within Pseudochirulus, the Australian P. herbertensis was recovered as the sister taxon to a New Guinean clade that included all other Pseudochirulus species. In the New Guinean clade, P. mayeri and P. caroli grouped together, these two grouped with P. forbesi, and these three grouped to the exclusion of P. canescens.

Individual genes

ML phylograms based on the individual genes were generally concordant with the concatenated analyses (Fig. 6). Individual petauroid families were always recovered as monophyletic except in analyses with Rag1 (Fig. 6E), which nested Tarsipedidae within Petauridae in a clade with Dactylopsila and Gymnobelideus. Within Petauridae, ENAM (Fig. 6C), IRBP (Fig. 6D), and vWF (Fig. 6F) grouped Gymnobelideus and Petaurus, BRCA1 (Fig. 6B) grouped Petaurus and Dactylopsila, and ApoB (Fig. 6A) grouped Gymnobelideus and Dactylopsila. Within Petaurus, all of the individual gene trees excepting ApoB recovered Petaurus as monophyletic, with P. breviceps and P. norfolcensis grouping to the exclusion of P. abidi. ApoB recovered P. breviceps as the sister taxon to all other petaurids (Fig. 6A). The three pseudocheirid subfamilies (Hemibelidinae, Pseudocheirinae, Pseudochiropsinae) were recovered as monophyletic in analyses with ApoB, BRCA1, ENAM, IRBP, and vWF (Fig. 6A–D, F), whereas analyses with Rag1 (Fig. 6E) failed to recover Petauroides + Hemibelideus.

Fig. 6.

RAxML phylograms for A. ApoB. B. BRCA1. C. ENAM. D. IRBP. E. Rag1. F. vWF.

Within Pseudocheirinae, all analyses with individual genes recovered Pseudochirulus as monophyletic. ENAM was the only gene segment that failed to recover the monophyly of New Guinean Pseudochirulus species, and instead placed P. canescens as the sister taxon to all other Pseudochirulus species.

Within Pseudochiropsinae, all genes except for IRBP supported a basal split between Pseudochirops archeri and all other taxa, whereas IRBP supported Pseudochirops monophyly. Monophyly of the New Guinean species of Pseudochirops (P. cupreus, P. albertisii, P. corinnae) was supported by BRCA1 and IRBP. All six genes supported a sister group relationship between P. cupreus and P. corinnae.

Molecular dating

Figure 5 shows the timescale for Petauroidea based on the partitioned BEAST analyses. Point estimates and 95% highest posterior densities (BEAST) or 95% credibility intervals (Multidivtime) for all nodes are given in Table 5. Dates for the soft-bounded, partitioned BEAST analyses were 0.03 million years older, on average, than soft-bounded, non-partitioned BEAST dates. Dates for the hard-bounded, partitioned BEAST analyses were 0.03 million years younger, on average, than hard-bounded, non-partitioned BEAST dates. Soft-bounded, partitioned BEAST dates were 0.10 million years younger, on average, than hard-bounded, partitioned BEAST dates. Soft-bounded, non-partitioned BEAST dates were 0.15 million years younger, on average, than hard-bounded, non-partitioned BEAST dates. Dates for partitioned Multidivtime analyses were 0.02 million years older, on average, than non-partitioned Multidivtime dates. BEAST dates were 1.2 million years younger, on average, than Multidivtime dates.

Table 5.

Divergence estimates based on Multidivtime and BEAST analyses

| Clade | Multidivtime | BEAST Partitioned | BEAST Non-partitioned | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partitioned | Non-partitioned | Soft Bounds | Hard Bounds | Soft Bounds | Hard Bounds | |

| Petauroidea | N/A | N/A | 35.71 (28.37–43.00) | 35.41 (28.82–42.77) | 35.69 (28.52–43.09) | 35.52 (28.85–42.85) |

| Tarsipedidae + Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae | 33.44 (28.41–39.11) | 33.36 (28.34–38.81) | 33.62 (27.07–40.86) | 33.23 (27.59–39.91) | 33.53 (26.74–40.40) | 33.28 (27.62–39.96) |

| Petauridae + Pseudocheiridae | 30.30 (26.00–35.12) | 30.03 (28.34–35.18) | 29.29 (23.17–35.39) | 29.13 (25.50–34.58) | 29.33 (23.44–35.70) | 29.21 (25.50–34.63) |

| Acrobatidae | N/A | N/A | 19.53 (13.52–25.63) | 20.38 (15.12–25.70) | 19.70 (13.71–26.20) | 20.31 (15.16–25.70) |

| Petauridae | 21.33 (17.54–25.17) | 20.74 (16.93–24.81) | 18.34 (13.83–23.17) | 18.89 (14.45–24.21) | 18.31 (13.60–22.98) | 18.80 (14.25–23.81) |

| Pseudocheiridae | 22.06 (18.29–25.41) | 20.55 (16.86–23.86) | 20.09 (15.85–24.52) | 20.50 (16.45–25.14) | 20.02 (15.69–24.33) | 20.57 (16.57–25.20) |

| Hemibelidinae + Pseudocheirinae | 20.46 (16.79–23.88) | 20.40 (16.78–23.65) | 18.39 (14.48–22.59) | 18.78 (14.89–23.15) | 18.31 (15.69–24.33) | 18.83 (14.90–23.13) |

| Hemibelidinae | 12.06 (9.25–15.01) | 12.20 (9.29–15.15) | 10.28 (7.17–13.47) | 10.51 (6.77–14.44) | 10.19 (7.23–13.47) | 10.49 (6.91–14.39) |

| Pseudocheirinae | 12.00 (9.30–14.92) | 12.02 (9.14–15.01) | 11.37 (8.66–14.29) | 11.72 (8.65–15.03) | 11.37 (8.70–14.28) | 11.82 (8.85–15.12) |

| Pseudochirulus | 5.85 (4.09–7.90) | 5.63 (3.87–7.66) | 5.81 (3.99–7.72) | 5.92 (4.09–7.99) | 5.83 (4.11–7.74) | 5.99 (4.10–8.05) |

| New Guinean Pseudochirulus spp. | 2.56 (1.56–3.85) | 2.35 (1.49–3.49) | 2.49 (1.62–3.44) | 2.52 (1.61–3.49) | 2.53 (1.68–3.50) | 2.58 (1.71–3.60) |

| Pseudochirulus forbesi + P. mayeri + P. caroli | 1.92 (1.10–2.94) | 2.09 (1.30–3.13) | 2.21 (1.39–3.08) | 2.23 (1.40–3.12) | 2.22 (1.43–3.10) | 2.26 (1.43–3.17) |

| Pseudochirulus mayeri + P. caroli | 1.46 (0.77–2.33) | 1.84 (1.21–2.81) | 1.92 (1.15–2.75) | 1.94 (1.16–2.81) | 1.93 (1.14–2.73) | 1.97 (1.19–2.86) |

| Pseudochiropsinae | 11.50 (8.78–14.52) | 12.12 (9.16–15.25) | 8.83 (6.13–11.75) | 8.61 (6.02–11.63) | 8.71 (6.19–11.57) | 8.68 (6.11–11.54) |

| Petropseudes + New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. | 9.71 (7.25–12.57) | 10.26 (7.55–13.21) | 7.18 (4.89–9.67) | 7.02 (4.82–9.54) | 7.11 (4.92–9.52) | 7.08 (4.92–9.58) |

| New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. | 8.93 (6.59–11.70) | 9.72 (7.12–12.64) | 6.67 (4.42–9.04) | 6.51 (4.36–8.89) | 6.61 (4.53–8.94) | 6.58 (4.50–8.94) |

| Pseudochirops cupreus + P. albertisii | 6.51 (4.56–8.86) | 6.69 (4.61–9.18) | 4.38 (2.65–6.25) | 4.28 (2.62–6.20) | 4.33 (2.76–6.18) | 4.33 (2.67–6.29) |

| Petaurus + Gymnobelideus | 19.98 (16.17–23.87) | 18.56 (14.77–22.50) | 16.05 (11.69–20.54) | 16.53 (12.24–21.39) | 15.97 (11.52–20.48) | 16.38 (12.21–21.19) |

| Dactylopsila | 7.51 (5.23–10.17) | 7.85 (5.34–10.91) | 5.30 (2.92–8.05) | 5.31 (2.99–8.05) | 5.25 (2.86–7.93) | 5.33 (3.08–8.10) |

| Petaurus | 2.40 (1.29–3.84) | 2.69 (1.68–4.10) | 3.17 (1.91–4.53) | 3.21 (1.94–4.61) | 3.16 (1.95–4.53) | 3.23 (2.01–4.66) |

| Petaurus breviceps + P. norfocelnsis | 0.97 (0.27–1.88) | 1.40 (0.75–2.31) | 1.73 (0.92–2.63) | 1.75 (0.95–2.66) | 1.73 (0.94–2.61) | 1.77 (0.96–2.69) |

All of the point estimates suggest that Petauridae split from Pseudocheiridae ∼30–29 Ma. Petaurids last shared a common ancestor ∼21–18 Ma. Within Petaurus, P. abidi last shared a common ancestor with P. norfolcensis + P. breviceps ∼3–2 Ma, and P. norfolcensis split from P. breviceps ∼2–1 Ma. Pseudocheirids last shared a common ancestor in the early Miocene (∼22–20 Ma). Hemibelidinae last shared a common ancestor with Pseudocheirinae ∼20–18 Ma. Diversification within the crown-clades Hemibelidinae, Pseudocheirinae, and Pseudochiropsinae commenced in the middle to late Miocene: Hemibelidinae (∼12–10 Ma); Pseudocheirinae (∼12–11 Ma); and Pseudochiropsinae (∼12–9 Ma). Within Pseudochiropsinae, the Australian Petropseudes dahli split from the New Guinean Pseudochirops species ∼10–7 Ma, and the three New Guinean species last shared a common ancestor ∼10–5 Ma. Within Pseudochirulus, the Australian P. herbertensis split from the New Guinean clade ∼6 Ma, and the New Guinean taxa last shared a common ancestor 3–2 Ma.

Ancestral state reconstructions

Figures 7 and 8 show the ancestral state reconstructions for geographic provenance and maximum elevation, respectively, based on SIMMAP (α = 3 and β = 2) and MacClade. SIMMAP posterior probabilities for ancestral state reconstructions are shown in Table 6.

Fig. 7.

A SIMMAP ancestral state reconstructions for geographic provenance. Posterior probabilities of ancestral state reconstructions are depicted with pie graphs at each node. B MacClade ancestral state reconstruction for geographic provenance.

Fig. 8.

A SIMMAP ancestral state reconstructions for maximum elevation. Posterior probabilities of ancestral state reconstructions are depicted with pie graphs at each node. B MacClade ancestral state reconstruction for maximum elevation.

Table 6.

SIMMAP results for ancestral state reconstructions of geographic provenance and maximum altitude occupied. Morphological priors were set to α = 3 and β = 2

| Clade | Clade Frequency | Posterior Probabilities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provenance | Altitude (meters) | |||||

| Australia | New Guinea | <1500 | 1500–30000 | >3000 | ||

| Pseudocheiridae | 1.0000 | 0.9694 | 0.0306 | 0.9853 | 0.0147 | 0.0000 |

| Hemibelidinae | 1.0000 | 0.9987 | 0.0013 | 0.9993 | 0.0007 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudocheirinae | 1.0000 | 0.9822 | 0.0178 | 0.9887 | 0.0113 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudochirulus | 1.0000 | 0.7476 | 0.2524 | 0.7843 | 0.2148 | 0.0008 |

| New Guinean Pseudochirulus spp. | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.8397 | 0.1603 |

| Pseudochirulus forbesi + P. mayeri + P. caroli | 0.7457 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0106 | 0.9894 |

| Pseudochirulus mayeri + P. caroli | 0.9595 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.1388 | 0.8612 |

| Pseudochiropinae | 1.0000 | 0.9154 | 0.0846 | 0.9400 | 0.0600 | 0.0000 |

| Petropseudes + New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. | 1.0000 | 0.1287 | 0.8713 | 0.1411 | 0.8589 | 0.0000 |

| New Guinean Pseudochirops spp. | 0.9748 | 0.0002 | 0.9998 | 0.0001 | 0.9995 | 0.0004 |

| Pseudochirops cupreus + P. albertisii | 1.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.9999 | 0.0000 | 0.9272 | 0.0728 |

| Hemibelidinae + Pseudochiropinae | 1.0000 | 0.9986 | 0.0014 | 0.9994 | 0.0006 | 0.0000 |

MacClade reconstructions recovered Pseudocheiridae, Hemibelidinae + Pseudocheirinae, Hemibelidinae, Pseudochiropsinae, and Pseudocheirinae as having Australian origins, whereas the New Guinean clades of Pseudochirops and Pseudochirulus, respectively, were reconstructed as having common ancestries in New Guinea (Fig. 7). In the SIMMAP analysis, the ancestral reconstructions for Pseudocheiridae, Hemibelidinae + Pseudocheirinae, Hemibelidinae, and Pseudocheirinae were reconstructed as having high posterior probabilities (>0.96) for an Australian origin. The ancestor of Pseudochirulus was most likely Australian in origin (∼0.75 posterior probability), and New Guinean species of Pseudochirulus were reconstructed as having a posterior probability of 1.00 for a New Guinea origin. The ancestor of Pseudochiropsinae was reconstructed as originating in Australia (∼0.91 posterior probability). In contrast to MacClade, SIMMAP reconstructed the common ancestor of Petropseudes and the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade as having a New Guinean origin (∼0.87). New Guinean Pseudochirops species were also reconstructed as New Guinean in origin (1.00 posterior probability).

MacClade and SIMMAP reconstructions (Fig. 8) both suggest that occupation of high elevations (>3000 m) occurred independently in Pseudochirops and Pseudochirulus. In Pseudochirops, occupation of elevations above 3000 m evolved on the terminal branch leading to Pseudochirops cupreus. In Pseudochirulus, high altitude occupation evolved in the ancestor of Pseudochirulus forbesi, Pseudochirulus mayeri, and Pseudochirulus caroli, with loss of high altitude occupation on the terminal branch leading to P. caroli (SIMMAP and acctran parsimony reconstructions; Fig. 8), or evolved independently on the branches leading to Pseudochirulus forbesi and Pseudochirulus mayeri (deltran parsimony reconstruction). The common ancestors of New Guinean Pseudochirulus and Pseudochirops, respectively, were both reconstructed as having maximum elevations between 1500 and 3000 m.

Discussion

Phylogenetic relationships

Petauroidea

Within Petauroidea, our results strongly support an association of Petauridae and Pseudocheiridae to the exclusion of Tarsipedidae. These results are consistent with other molecular studies (Kavanagh et al. 2004; Phillips and Pratt 2008; Meredith et al. 2009a, c).

Petauridae

Our analyses grouped Petaurus and Gymnobelideus to the exclusion of Dactylopsila with strong support. This result is consistent with morphology (Smith 1984; Aplin and Archer 1987; Archer 1984), chromosomal characters (McKay 1984), brain encephalization (Nelson and Stephan 1982), serological data (Kirsch and Calaby 1977; Kirsch 1977), single-copy DNA–DNA hybridization studies (Springer et al. 1994), and classifications (Kirsch 1977; Archer 1984) that place Petaurus and Gymnobelideus in the subfamily Petaurinae. In contrast, Meredith et al. (2009a) found moderate support for an association of Dactylopsila and Gymnobelideus with a data set that included one less gene (ENAM) and one fewer Petaurus species. Baverstock et al. (1990a) and Edwards and Westerman (1995) also found support for Dactylopsila + Gymnobelideus based on MC’F data and single copy DNA-DNA hybridization results, respectively. The ENAM gene provides additional support for Petaurus + Gymnobelideus and may explain the difference between the present results and Meredith et al.’s (2009a) earlier study.

Pseudocheiridae

Our analysis included 13 of 16 (Nowak and Dickman 2005) or 17 (Groves 2005) extant species of Pseudocheiridae, and representatives of all six genera. Missing species (following Groves 2005) included three species of Pseudochirulus (P. cinereus, P. schlegeli, P. larvatus) and Pseudochirops coronatus. Of these, P. cinereus has previously been recognized as a subspecies of P. herbertensis (e.g., Tate 1945); P. schlegeli and P. larvatus have previously been recognized as subspecies of P. forbesi (e.g., Tate 1945); and P. coronatus has previously been recognized as a subspecies of Pseudochirops albertisii (e.g., Tate 1945). Previous work therefore suggests that holes in our taxonomic sampling are less important for evaluating intergeneric relationships than for assessing intrageneric relationships within Pseudochirulus and Pseudochirops.

Groves (2005) recognized three pseudocheirid subfamilies: Pseudocheirinae (Pseudocheirus, Pseudochirulus, Petropseudes); Hemibelidinae (Hemibelideus, Petauroides), and Pseudochiropsinae (Pseudochirops). Previous phylogenetic analyses are generally in agreement with this classification (Baverstock et al. 1990b; Springer et al. 1992; Springer 1993; Kirsch et al. 1997; Meredith et al. 2009a), except that Petropseudes groups with Pseudochirops rather than with Pseudocheirus and Pseudochirulus (Baverstock et al. 1990b; Springer 1993). Hemibelidinae is supported by karyology (Hayman and Martin 1974; McKay 1984; McQuade 1984), microcomplement fixation (Baverstock1984; Baverstock et al. 1987, 1990ba), craniodental cladistics (Archer 1984; Springer 1993), single-copy DNA–DNA hybridization (Springer et al. 1992), and nuclear DNA (Meredith et al. 2009a). Pseudocheirus + Pseudochirulus is supported by single-copy DNA–DNA hybridization (Springer et al. 1992; Kirsch et al. 1997) and nuclear DNA (Meredith et al. 2009a). Finally, a clade comprising Pseudochirops and Petropseudes is supported by low chromosome numbers (Hayman and Martin 1974; Murray et al. 1990), dental characters (Archer 1984; Springer 1993), microcomplement fixation (Baverstock et al. 1987, 1990b), and nuclear DNA (Meredith et al. 2009a). We find robust support for all three of these lineages. We also find strong support for the basal split between Pseudochiropsinae and all other pseudocheirids that was recovered by Meredith et al. (2009a). Based on the congruence of multiple phylogenetic studies, we recommend a revised classification for pseudocheirids that recognizes the same three subfamilies as Kirsch et al. (1997) and Groves (2005), but modifies the taxonomic composition of Groves’ Pseudocheirinae and Pseudochiropsinae by transferring Petropseudes dahli from Pseudocheirinae to Pseudochiropsinae.

Craniodental characters (Springer 1993) and microcomplement results (Baverstock et al. 1990b) have supported Pseudochirops monophyly. Craniodental analyses suggested that Pseudochirops albertisii, P. cupreus, and P. archeri group together to the exclusion of P. corinnae, whereas microcomplement fixation data suggested P. albertisii, P. archeri, and P. corinnae group to the exclusion of P. cupreus. In contrast to cladistic analyses of craniodental characters and microcomplement fixation results, we find strong support for Pseudochirops paraphyly, i.e., Petropseudes dahli and the New Guinean species of Pseudochirops (albertisii, cupreus, corinnae) group together to the exclusion of Pseudochirops archeri. Our finding that Pseudochirops is paraphyletic supports Meredith et al.’s (2009a) proposal that Petropseudes dahli be recognized as Pseudochirops (Petropseudes) dahli. Among New Guinean Pseudochirops species, an association of P. cupreus and P. albertisii was previously proposed by Tate (1945).

Within Pseudochirulus we find strong support for the basal split between the Australian P. herbertensis and a New Guinean clade comprising the remainder of Pseudochirulus species included in our study. Within the monophyletic New Guinean clade, our results suggest that P. forbesi groups with both P. mayeri and P. caroli to the exclusion of P. canescens. DNA-DNA hybridization studies suggested P. forbesi and P. canescens group together to the exclusion of P. herbertensis (Springer et al. 1992), but MC’F data (Baverstock et al. 1990b) suggested an association of P. herbertensis and P. forbesi to the exclusion of both P. mayeri and P. canescens. Cladistic analyses with craniodental analyses (Springer 1993) recovered a monophyletic New Guinean Pseudochirulus clade with Dollo parsimony, and in a subset of analyses with Wagner parsimony, but not with Camin-Sokal parsimony.

Petaurid divergence times

Our point estimates for the split between the Petaurus abidi and Petaurus breviceps + Petaurus norfolcensis are in the range of 3–2 Ma in the late Pliocene. These estimates are 6–10 million years younger than Malekian et al.’s (2009) estimate for this split (∼12–9 Ma). Malekian et al. (2009) used BEAST to estimate divergence dates based on two mitochondrial protein-coding genes (ND2, ND4), but the only constrained node in Malekian et al.’s (2009) analyses was the split between P. breviceps and P. norfolcensis, which Malekian et al. (2009) constrained to have a minimum of 4.46 million years ago based on a fossil identified as similar to P. norfolcensis. However, this ignores Turnbull et al.’s (2003) more recent assessment that Hamilton Local Fauna fossils belonging to Petaurus may represent as many as three species (near P. norfolcensis, P. breviceps, and P. australis) or as few as one highly variable species. In contrast, our analyses were based on nuclear genes rather than mitochondrial genes, and employed multiple constraints, but did not impose a minimum constraint on the divergence between P. norfolcensis and P. breviceps given Turnbull et al.’s (2003) uncertain placement of Petaurus fossils from the Hamilton Local Fauna.

Malekian et al.’s (2009) molecular divergence dates suggest a much earlier origin for Petaurus (24–18 Ma) than does the fossil record (oldest Petaurus fossils are ∼4.46 million years). Our taxon sampling did not include Petaurus australis, which prevented us from dating the most recent common ancestor of Petaurus, but did include representatives of the other major lineages that were sampled by Malekian et al. (2009). Malekian et al.’s (2009) divergence times for P. abidi to P. breviceps + P. norfolcensis (∼12–9 Ma) and P. breviceps to P. norfolcensis (∼9–7 Ma) are Miocene in age and are compatible with connectivity between northern Australia and southern New Guinea during the late Miocene when sea-level reductions (Byrne et al. 2008) and emergent land bridges (Hall 2001; Malekian et al. 2009) may have facilitated dispersal between New Guinea and Australia. Malekian et al. (2009: 11) further concluded that among Petaurus species included in their study there was no evidence of dispersal events during the Pleistocene when “Ice Age sea-level reductions led to cycles of land bridge connectivity between New Guinea and Australia.” In contrast, our point estimates for the separation of P. breviceps and P. norfolcensis are all in the Pleistocene. Coupled with Malekian et al.’s (2009) reconstruction of an ancestral area of New Guinea for this node, our divergence time estimates suggest that the ancestor of P. norfolcensis likely dispersed from New Guinea to Australia when there was land bridge connectivity between New Guinea and Australia during the Pleistocene.

Pseudocheirid divergence times, biogeography, and altitudinal zonation

In contrast to all previous analyses that have examined pseudocheirid relationships, we find strong support for the monophyly of New Guinean Pseudochirulus and New Guinean Pseudochirops, respectively. In a parsimony framework, the monophyly of each New Guinean cohort can be explained by a single dispersal event. In contrast, SIMMAP reconstructions favor a New Guinean ancestor of the clade that includes the Australian Petropseudes dahli and the New Guinean Pseudochirops species (Fig. 7; Table 6). This scenario requires back dispersal to Australia for the ancestor of the Petropseudes lineage. The only fossil described for the Petropseudes lineage is a molar tooth fragment from the Pliocene (∼5.3–2.6 Ma) Riversleigh Rackham Roost site (Archer et al. 1997, 2006). This fossil postdates our divergence estimates for the common ancestor of Petropseudes and the New Guinean Pseudochirops species (10–7 Ma), allowing enough time for the back dispersal. Petropseudes differs from all other pseudocheirids in that it inhabits rocky outcrops in northern Australia and is more terrestrially adapted than its cousins, climbing trees only at night to feed (Nowak and Dickman 2005). The SIMMAP reconstruction of a New Guinean common ancestry for Petropseudes and the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade (Fig. 7A) may be a consequence of the short branch leading from this ancestor to the common ancestor of the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade (Fig. 3). This branch was reconstructed as representing less than one million years in all Multidivtime and BEAST analyses (Table 5). Thus the probability of two separate dispersal events on longer branches that represent more time, one on the branch leading to Petropseudes and New Guinean Pseudochirops, and a second on the branch leading to Petropseudes, was reconstructed by SIMMAP as more likely than a single dispersal on the shorter branch leading to the New Guinean Pseudochirops species.

Our analyses suggest that the ancestor of the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade arrived in New Guinea as early as ∼12 million years ago (SIMMAP ancestral reconstructions; Multidivtime non-partitioned date for the split between Pseudochirops archeri and other members of Pseudochirops plus Petropseudes), and no later than ∼6.5 million years ago (MacClade ancestral reconstructions; hard-bounded, partitioned BEAST date for the common ancestor of New Guinean Pseudochirops) in the late Miocene, and that the ancestor of New Guinean Pseudochirulus arrived in New Guinea 6–2 Ma. Aplin et al. (1993) suggested multiple dispersal events between Australian and New Guinean in both Pseudochirulus and Pseudochirops in the late Miocene (12–10 Ma) and Pliocene (4.7–2.7 Ma). Kirsch and Springer (1993) analyzed a smaller subset of species for each genus and suggested that the common ancestors of New Guinean Pseudochirulus and Pseudochirops species, respectively, both arrived in New Guinea ∼10 Ma. As mentioned above, Hall (2001) and Byrne et al. (2008) provide evidence for lower sea levels and land bridges between northern Australia and southern New Guinea in the late Miocene between ∼10–7 Ma. Our molecular estimates for the dispersal of Pseudochirops species between Australia and New Guinea are compatible with dispersal during the late Miocene when land bridges may have existed. Pseudochirulus probably reached New Guinea at a later time, possibly in the early Pleistocene when sea levels were once again lower and land bridges connected Australia and New Guinea.

In contrast to our results, which suggest that pseudocheirids reached New Guinea no sooner than 12 Ma, relaxed molecular dates for phalangerids suggest that the ancestor of Phalangerini + Ailurops ursinus + Strigocuscus celebensis dispersed from Australia to the New Guinean region between ∼29 Ma and ∼19 Ma (Raterman et al. 2006), or between ∼17 Ma and ∼14 Ma (Meredith et al. 2009a). The earlier dispersal of phalangerids than pseudocheirids to New Guinea and surrounding islands may reflect the superior dispersal and colonization abilities of the former (Flannery 1995a), which is evidenced by the presence of endemic phalangerid species, but not pseudocheirid species, on oceanic islands such as Woodlark Island (Flannery 1995a). In contrast to pseudocheirids, which have diets that are specialized for folivory, phalangerids typically have more diverse diets that include a wide variety of leaves, fruit, flowers, and in some cases even meat when available (Hume et al. 1993; Flannery 1995a). The more generalist diet of phalangerids may predispose them to successful colonization. Finally, the dispersal abilities of some pseudocheirids may be restricted by their largely or strictly arboreal lifestyles and reluctance to come to the ground (Pahl et al. 1988; Laurance 1990; Laurance and Laurance 1999).

Recent geological evidence suggests that New Guinea has been shaped by two orogenic events. The first event was the Peninsular orogeny, which resulted in the Papuan Peninsula during the Oligocene (35–30 Ma). The mountainous spine of New Guinea, in turn, was formed by the Central Range orogeny that commenced ∼15 Ma when small isolated islands appeared (Cloos et al. 2005; van Ufford and Cloos 2005). The orogeny in the western Central Range began in earnest between 15 and 12 Ma, when the cordillera attained elevations that were hundreds of meters high. Between 12 and 8 Ma, proto-New Guinea continued to widen and reached elevations up to ∼2 km. The most dramatic period of vertical uplift occurred between 8 and 4 Ma, when the core of the orogenic belt rose upwards and increased in width. Volcanism in the western Central Range began at ∼7 Ma. At ∼5 Ma, the cordillera of western New Guinea included topography between 3000 and 5000 m high (Cloos et al. 2005: fig. 19). Between 4 Ma and the present, current day altitudes and geography were established. Orogenic events in the eastern Central Range are sequentially younger by about three million years than those for the western Central Range—a result of the orientation of the plates and propagation of the tear in the subducting Australian plate (Cloos et al. 2005; van Ufford and Cloos 2005).

Relaxed clock dates for cladogenesis within the New Guinean Pseudochirops clade are in the range of 9.7–6.5 Ma (Multidivtime) or 6.7–4.3 Ma (BEAST) and are generally coincident with the uplift of the central cordillera and other highlands of New Guinea. Diversification within the New Guinean Pseudochirulus clade has occurred in the last 2.5 Ma and postdates the origin and establishment of the central cordillera and other highlands in New Guinea. This suggests that Pseudochirulus species diversified into habitats with pre-existing, altitudinal differentiation.

Ancestral reconstructions suggest that cladogenic events in New Guinean Pseudochirops occurred at elevations that were below 1500 m, or between 1500 and 3000 m. Occupation of altitudes above 3000 m is a derived feature that evolved in Pseudochirops curpreus. Occupation of high elevations in P. cupreus is associated with scrub and herbfield at 3700 m in the Prinz Wilhelm V Range in Irian Jaya (Flannery 1995b). In Pseudochirulus, high altitude occupation (>3000 m) either evolved in the ancestor of P. forbesi, P. mayeri, and P. caroli, with subsequent loss in P. caroli, or evolved independently in P. mayeri and P. forbesi. P. forbesi is most common between 1200 and 2800 m, but has been recorded as high as 3800 m (Helgen 2007a, b). P. mayeri inhabits montane forests between 1200 and at least 4200 m along the central cordillera of New Guinea, and is most abundant in upper montane, moss forests that are above 2000 m, and in some cases 3000 m (Flannery 1995b; Helgen 2007a, b). In conjunction with its occupation of moss forests, P. mayeri has a unique diet among pseudocheirids that includes leaves, mosses, ferns, lichens, fungi, and pollen (Hume et al. 1993; Flannery 1995b).

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(TXT 153 kb)

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to the Australian Museum for providing tissue samples of Pseudochirulus caroli and Pseudochirops albertisii. M.S.S. acknowledges support from the NSF AToL program (EF06298660). We also thank the Medical Scholars Program, and the Mentoring Summer Research Internship Program, for providing support to M.M. Two anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Amrine-Madsen H, Scally M, Westerman M, Stanhope MJ, Krajewski C, Springer MS. Nuclear gene sequences provide evidence for the monophyly of australidelphian marsupials. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003;28:186–196. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin KP, Archer M. Recent advances in marsupial systematics with a new syncretic classification. In: Archer M, editor. Possums and Opossums: Studies in Evolution. Chipping Norton: Surrey Beatty and Sons; 1987. pp. xv–xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Aplin KP, Baverstock PR, Donnellan SC. Albumin immunological evidence for the time and mode of origin of the New Guinean terrestrial mammal fauna. Sci New Guinea. 1993;19:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- Archer M. The Australian marsupial radiation. In: Clayton G, editor. Archer M. Perth: Vertebrate Zoogeography and Evolution in Australasia. Hesperian Press; 1984. pp. 477–516. [Google Scholar]

- Archer M, Arena DA, Bassarova M, Beck RMD, Black K, Boles WE, Brewer P, Cooke BN, Crosby K, Gillespie A, Godthelp H, Hand SJ, Kear BP, Louys J, Morrell A, Muirhead J, Roberts KK, Scanlon JD, Travouillon KJ, Wroe S (2006) Current status of species-level representation in faunas from selected fossil localities in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area, northwestern Queensland. Alcheringa Spec Issue 1:1–17

- Archer M, Arena R, Bassarova M, Black K, Brammall J, Cooke B, Creaser P, Crosby K, Gillespie A, Godthelp H, Gott M, Hand SJ, Kear B, Krikmann A, Mackness B, Muirhead J, Musser A, Myers T, Pledge N,Wang Y,Wroe S (1999) The evolutionary history and diversity of Australian mammals. Aust Mammal 21:1–45

- Archer M, Hand SJ, Godthelp H, Creaser P (1997) Correlation of the Cainozoic sediments of the Riversleigh World Heritage Fossil Property, Queensland, Australia. In: Aguilar J-P, Legendre S, Michaux J (eds) Actes du Congres BiochroM’97, Montpellier, L’école Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Institut de Montpellier, pp 131–152

- Barker FK, Lutzoni FM. The utility of the incongruence length difference test systematic biology. Syst Biol. 2002;51:625–637. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassarova M, Archer M. Living and extinct pseudocheirids (Marsupialia, Pseudocheiridae): phylogenetic relationships and changes in diversity through time. Aust Mammal. 1999;21:25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baverstock PR, Birrell J, Krieg M. Albumin immunological relationships of the Diprotodontia. In: Archer M, editor. Possums and Opossums: Studies in Evolution. New South Wales: Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton; 1987. pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Baverstock PR, Krieg M, Birrell J. Evolutionary relationships of Australian marsupials as assessed by albumin immunology. Aust J Zool. 1990a;37:273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Baverstock PR, Krieg M, Birrell J, McKay GM. Albumin immunologic relationships of Australian Marsupials II.* The Pseudocheiridae. Aust J Zool. 1990b;38:519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Beck R, Godthelp H, Weisbecker V, Archer M, Hand SJ. Australia’s oldest marsupial fossils and their biogeographical implications. Plos One. 2008;3:e1858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton MJ, Donoghue PCJ. Paleontological evidence to date the tree of life. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:26–53. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]