Summary

For years, DC biologists have oscillated between two seemingly antagonistic ideas: functional specialization (division of labor) of DC subsets and plasticity (multitasking). More recently, a third hypothesis is gathering support: crosstalk between functionally distinct DC subsets. This reveals a previously unappreciated hierarchy of organization within the DC system, and provides a conceptual framework to understand how cooperation between functionally distinct, yet plastic, DC subsets can shape adaptive immunity and immunological memory. Here we review recent advances in this area.

Introduction

The immune system is constantly faced with choices. When confronted with a microbe, it must first decide whether to respond or not to respond. If it chooses to respond, then it must decide what kind of response to launch. A hallmark of the mammalian immune system is its ability to launch qualitatively distinct types of responses against different pathogens. Thus, immune responses against T-cell-dependent antigens display striking heterogeneity with respect to the cytokines made by T-helper cells and the class of antibody secreted by B cells. In response to intracellular microbes, CD4+ T-helper (Th) cells differentiate into Th1 cells, which produce IFNγ; in contrast, helminths induce the differentiation of Th2 cells, whose cytokines (principally IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 & IL-10) induce IgE and eosinophil-mediated destruction of the pathogens (1, 2). Furthermore, Th17 cells which secrete interleukin-17 were recently described, and are thought to mediate protection against fungi (3, 4). Finally, T regulatory cells, which suppress T cell responses, are thought to maintain “self-tolerance” to host antigens. T regulatory cells can also be induced by several pathogens and microbial stimuli, presumably to evade the immune system (5, 6). While there is much knowledge about the cytokines produced early in the response, and the transcription factors that determine Th polarization, the early “decision-making mechanisms,” which result in a given type of immune response remain poorly understood. There is now ample evidence for a fundamental role for dendritic cells [DCs] in this process (7–11). DCs express a wide array of pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which enable them to “sense” microbial stimuli and to respond to infections (11–15). Research over the past decade has emphasized two important ways in which DCs regulate adaptive immunity: (1) distinct subsets of DCs which are specialized to differentially bias the T-helper response; and (2) the “plasticity” in DC function that enables DCs to flexibly respond to a diverse range of microbial and environmental stimuli. Emerging evidence points to a previously unappreciated facet of how DCs influence the immune response: DC-DC crosstalk. In the present article we review recent work which suggests that intercellular cross-talk between distinct DC subsets, either synergistic or antagonistic, exerts a potent influence on the immune response. Some excellent recent reviews have provided comprehensive analysis of recent advances in human DC subsets (7–9), so the present review will mainly focus on murine DC subsets. Furthermore, the goal of the present review is not to provide a comprehensive survey of murine DC subsets, but rather to focus on key findings pertaining to their division of labor, plasticity and cross-talk between themselves.

Dendritic Cell Subsets

DCs represent a complex “immunological system,” comprised of several subsets that are distributed in different microenvironments within the body, and that are equipped to sense different types of pathogens, and to modulate distinct classes of immune responses (7–11). The lineage relationship between these different subsets, their responsiveness to different pathogens, and the mechanisms by which they influence the adaptive immune response are areas of intense investigation and have been reviewed extensively (8–10). This section will summarize our understanding of the roles played by murine DC subsets in modulating immune responses.

When is a DC subset really a subset?

In mice there are at least 6 different subsets of DCs, in the “steady state.” In discussing DC subsets, a critical question is what one really means by a “subset.” Traditionally DC biologists have used a combination of variables including developmental origins and biological properties (e.g. phenotype, function, and micronevironmental localization) to sub-divide DCs into subsets. However opinions vary as to what combination of variables is best suited for this purpose. Classification based on development can be problematic, since the developmental pathways of DCs are not yet fully understood. For instance, earlier work suggesting that splenic CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs develop from distinct precursors supported their classification into distinct subsets, but has been challenged by subsequent work that demonstrates that both of these subsets can develop from the early clonal lymphoid and myeloid precursors (10). In fact, it is increasingly clear that the birfurcation of DC development into distinct streams that give rise to distinct DC subsets occurs relatively late in DC development, since precursors that yield splenic CD11c+ classical DCs versus plasmacytoid DCs can be isolated from the spleens (10, 16). Classifications based on phenotype whilst useful, can also pose complications. For example, as will be discussed later, intestinal DC subsets have been defined by different groups using different phenotypic markers (e.g. CX3CR1 versus CD103 versus the conventional markers such as CD11b and CD8α [17, 18]), thus giving rise to some confusion as to exactly which subset is being studied. Furthermore, in some cases, a sub-population of DC might have only a very subtle phenotypic difference from a different sub-population, and in this case the demarcation of such sub-populations as distinct subsets becomes more arbitrary. For example, the CD8α− DC subset can be sub-divided further into CD4+ versus CD4− DCs, which are phenotypically and functionally very similar (11). Thus, perhaps the most informative way to classify DCs is based on their biological properties, microenvironmental localization, and phenotype. For example, as will be discussed below, CD8α + DCs and CD8α− DCs in the spleen differ with respect to their phenotype, functions and microenvironmental localization, and thus can be considered to be two different subsets.

DC subsets: Phenotype, function and microenvironmental localization [Table 1]

TABLE 1.

Major DC subsets in mice

| Major DC Subsets in mice | CD8α+ CD11b− DCs | CD8α− CD11b+ DCs | Plasmacytoid DCs | Langerhans DCs | Dermal DCs | CD8α− CD11b− DCs | Monocyte derived DCs (During Inflammation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | CD11chighCD8α+

CD11b− DEC205+ CD4− |

CD11chighCD8α−

CD11b+ DEC205− CD4+ (subset) |

CD11cintCD8α+/−

CD11b− B220+ Gr-1+ |

CD11chighCD8αdull

DEC205high Langerin+ |

CD11chighCD8α−

CD11b+ DEC205+ |

CD11chighCD8α−

CD11b− DEC205+ CD4− |

CD11cintCD8α−

CD11b+ DEC205+ CD4− |

| Organ | Spleen, LN, PP, LP, MLN | Spleen, LN, PP, LP, MLN | Spleen, LN, PP, LP(?), MLN | Epithelium of skin LN, MLN | Dermis of skin LN, MLN | PP | Inflamed spleen, LN |

| Microenvironment | T cell rich areas | Marginal zones(spleen); subcapsular sinus (LN) subepithelial dome (PP) | Marginal zones(spleen); T cell rich areas of LN | Epithelium of skin T cell rich areas of LN | Dermis of skin T cell rich areas of LN | T cell rich areas subepithelial dome; follicle associated epithelium, B cell follicle | ? |

| Cytokines | High IL-12p70

Low IL-10 |

Low IL-12p70

High IL-10 |

IFN-α (except in PP) | ? | ? | High IL-12

p70 Low IL-10 |

? |

| T-helper responses | Th1 (except in LP) | Th2 (except in LP where they prime Th17) | Th1 or T regulatory | Th1 | ? | ? | ? |

| Cross-presentation to CD8α+ T cells | ++++ | - | - | - | - | ? | ? |

LN, lymph node; PP, Peyer’s patch; LP, lamina propia; MLN, mesenteric lymph node.

DCs in the spleens and lymph nodes of mice, in the steady state, are characterized by the expression of the integrin-α CD11c and class II MHC. In the spleens of mice, at least 3 subsets of DCs have been described (Table 1, 10, 11, 14):

CD11chighCD8α+ CD11b− DEC205+ DCs [so called “CD8α+ lymphoid” DCs]

CD11chighCD8α− CD11b+ DEC205− DCs [so called “CD8α− myeloid” DCs]. This subset can be further divided into two, based on the expression of CD4 or 33D1.

CD11cintermediateCD8α+/− CD11b−B220+ Gr-1+ [plasmacytoid DCs]

In the lymph nodes of mice, in addition to these 3 or 4 subsets, there are at least 2 other subsets (Table 1, 10, 11, 14):

CD11chighCD8αdullDEC205high Langerin+ [Langerhans cell-derived DCs (LCDCs)]

CD11chighCD8α− CD11b+ DEC205+ [dermal DCs]

The CD11chighCD8α+ DCs are localized in the T-cell rich areas of the spleen and lymph nodes and have some predetermined capacity to secrete abundant IL-12(p70) and stimulate Th1 responses (10, 11, 14, 19–21). In contrast, CD8α− DCs are localized in the marginal zones of the spleen, and the subcapsular sinuses of the lymph nodes, do not generally secrete much IL-12(p70), but rather secrete IL-10, and have been shown to induce Th2 responses (20, 21). The intrinsic functional differences between these subsets was elegantly demonstrated in vivo, by targeting an antigen to a specific subset using antibodies that bound to a specific receptor on each of the subsets (22). With regards to cross-presentation of particulate or soluble protein antigens to CD8+ T cells, it appears that the CD8α+ DCs are more efficient (23, 24). Furthermore, these DCs are preferentially able to endocytose dying cells in vivo, and cross-present cellular antigens to both CD8+ T cells (25). This is consistent with the differential antigen-processing ability of CD8α+ versus CD8α− DC subsets (26). However, both the CD8α+, and the CD8α− DC subsets are capable of cross-presenting antigens, after activation via the Fcγ receptor (27). Thus, any innate differences in the ability of the distinct DC subsets to cross-present can be overcome by particular modes of activation.

The CD11chighCD8αdullDEC205high Langerin+ DCs are Langerhans cell derived DCs (LCDCs), which have migrated to the lymph nodes, from the skin (9–11). The CD11chighCD8α− CD11b+DEC205+ DCs represent dermal DCs which have migrated to the LN from the dermis of the skin (9–11). Plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) can be stimulated to rapidly secrete copious amounts of interferon-α [IFN-α] (28–30). In addition to these subsets which are present in the steady state, it is now clear that TLRs are expressed in early hematopoeitic cells (31), and that TLR-mediated inflammation can influence DC development (10, 16). For example, CCR2+ Ly6C+ inflammatory monocytes develop into DCs in an inflammatory environment (16, 32–34).

In the intestine, DCs have been described in four major locations: Peyer’s patches (PP), lamina propria (LP), and the mesenteric LNs. Four different subsets of DCs have been described in the PP (18):

CD11cbrightCD8α+CD11b−CCR6− DCs, which like their CD11cbrightCD8α+ counterparts in the spleen and LNs (19–21), are situated in the T cell rich interfollicular region (IFR), can be induced to secrete high amounts of IL-12p70 and stimulate Th1 responses (18, 35, 36).

CD11cbrightCD8α−CD11b+CCR6− DCs, which like their CD11cbrightCD8α+ counterparts in the spleen and LNs (19–21), are situated in the subepithelial dome (SED) and can be induced to secrete abundant IL-10, and to stimulate Th2 responses (18, 35, 36).

CD11cbrightCD8α−CD11b−CCR6+ which are located in both the IFR and SED and stimulate Th1 responses (18, 36).

CD11cintermediateCD8α+/− CD11b−B220+ Gr-1+ plasmacytoid DCs. However unlike pDCs from other tissues, PP pDCs appear incapable of producing significant levels of type I IFNs (37), perhaps via three regulatory factors associated with mucosal tissues, PGE(2), IL-10, and TGFβ (37).

In the LP, recent work shows two major subsets of DCs: CD11cbrightCD8αdullCD11b+ DCs which stimulate Th17 responses (38), and CD11cbrightCD8α+CD11b− whose function is unclear at present (38, 39). In addition, pDCs have been described in the LP (39). LP DCs have been observed to extend dendrites between epithelial cells into the intestinal lumen (40).

In addition to this “traditional” way of classifying DCs, recent work has used the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 (the receptor of CX3CL1, fractalkine) and the α integrin CD103 to classify DCs (18, 41–45). Thus mice, in which the gene for green fluorescent protein is “knocked in” to the CX3CR1 locus has revealed large numbers of CX3CR1+ DCs in the LP (41). The correlation between CX3CR1, CD103 and the “traditionally defined” subsets is at present murky, but our recent work suggests that CD11cbrightCD8αdullCD11b+ DCs in the LP are CX3CR1+ and mostly CD103 intermediate (38). However, a minor subset within the CD11cbrightCD8α−CD11b+ DCs in the LP express very high levels of CD103. In contrast, CD11cbrightCD8α+CD11b− DCs in the LP are CX3CR1- and CD103bright (38). The functional properties of these various DC subsets are only now beginning to be appreciated. Recent work from several groups suggest that CD103 expressing DCs in the MLN (45), and DCs in the LP some of which express CD103 (44), induce T regulatory cells. This seems to be dependent on a mechanism involving retinoic acid (44–47). In the MLN, in addition to the CD11cbrightCD8α+CD11b− and CD11cbrightCD8α−CD11b+ two additional DC subsets can be defined using the differential expression of CD4 and DEC-205 (18). However, the functional significance of these remains unknown.

Dendritic Cell Plasticity

Plasticity in response to microbial stimuli

The ability to respond rapidly to invading pathogens is a hallmark of DC function. It has been known for sometime that DCs cultured in vitro can be “conditioned” by microbial stimuli, or cytokines (10–14, 48). DCs like many other immune cells express a variety of pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), such as TLRs non-TLRs (which includes C-type lectin like receptors or CLRs, NOD-like receptors or NLRs and RIG-I like receptors or RLRs), which allows them to sense a myriad of microbial stimuli and initiate an innate response (11–15). In fact, recent work suggests that direct activation of DCs by pathogen derived stimuli via TLRs is necessary to promote full DC activation and stimulation of Th1 or Th2 cells (11–15). Inflammatory mediators originating from nonhematopoietic tissues or from radioresistant hematopoietic cells seem neither sufficient nor required for full DC activation in vivo (49). Most work has focused mainly on TLRs, but emerging evidence suggests a role for non-TLRs also in modulating DC function. Numerous recent articles (11–15, 50) have reviewed the roles played by TLRs, C-type lectins, NOD-like recptors and RIG-I and MDA-5 in this process, so we will not discuss this further here.

Plasticity in response to tissue derived signals

Although direct sensing of pathogen stimuli seems to be critical for the elicitation of full DC activation and effective polarization of T helper responses (49), a growing body of evidence suggests that cytokines and chemokines in the local microenvironment can also modulate DC function and influence the immune response. Early in vitro experiments suggest that DCs cultured with IL-10 or TGF-β, induce Th2 or T regulatory responses while DCs cultured with IFN-γ induce potent Th1 responses (reviewed in 11–15, 48). These observations raised the possibility that the microenvironment potently influences DC function. In particular, emerging evidence suggests that stromal cells in the tissue microenvironment can condition DCs in a microenvironment-specific manner. Consistent with this, Peyer’s patch or respiratory tract DCs were shown to prime Th2 responses, while total spleen DCs primed Th1/Th0 responses (reviewed in 11–15, 48).

Recent studies have begun to provide direct evidence for the role of stromal cells in conditioning the function of DCs. For example, recent work suggests that splenic or endothelial stromal cells can program the differentiation of DCs into cells that induce T regulatory cells (51, 52). In the case of Th2 differentiation, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cell derived cytokine strongly activates DCs, to stimulate inflammatory Th2 cells, via an OX40-L dependent mechanism (53). In the intestine, under steady state conditions, TSLP is produced by intestinal epithelial cells and influences DCs to prime Th2 responses (54). In addition, over expression of TSLP produced by keratinocytes or airway epithelial cells correlates with Th2 diseases such as atopic dermatitis and asthma (55). In contrast to these effects on Th2 responses, in the human thymus, TSLP expressed by Hassal’s corpuscles is known to instruct DCs to select T regulatory cells (56). These observations may explain classical observations that the route of antigen delivery is a crucial determinant of the type of immune response; thus inhaled antigens induce a Th2 response, while antigens injected subcutaneously induce a Th1 response.

Dendritic Cell-Dendritic Cell Cross Talk

Although the functional specializations and plasticity of DCs have been well appreciated, recent work suggests possible mechanisms of crosstalk between distinct DC subsets (Figure 1). Yoneyama et al showed that during herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in mice, that lymph node-recruited pDCs cooperate with local classical DCs to generate antiviral cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (57). Although pDCs alone failed to induce CTLs, in vivo depletion of pDCs impaired CTL-mediated virus eradication. Classical lymph node DCs from pDC-depleted mice showed impaired antigen presentation to prime CTLs. Transferring circulating pDC precursors from wild-type, but not CXCR3-deficient, mice to pDC-depleted mice restored CTL induction by impaired classical lymph node DCs. In vitro co-culture experiments revealed that pDCs provided help signals that recovered impaired lymph node DCs in a CD2- and CD40L-dependent manner. pDC-derived IFN-α further stimulated the recovered lymph node DCs to induce CTLs. Therefore, the help provided by pDCs for lymph node DCs in primary immune responses seems to be pivotal to optimally inducing anti-HSV CTLs (57).

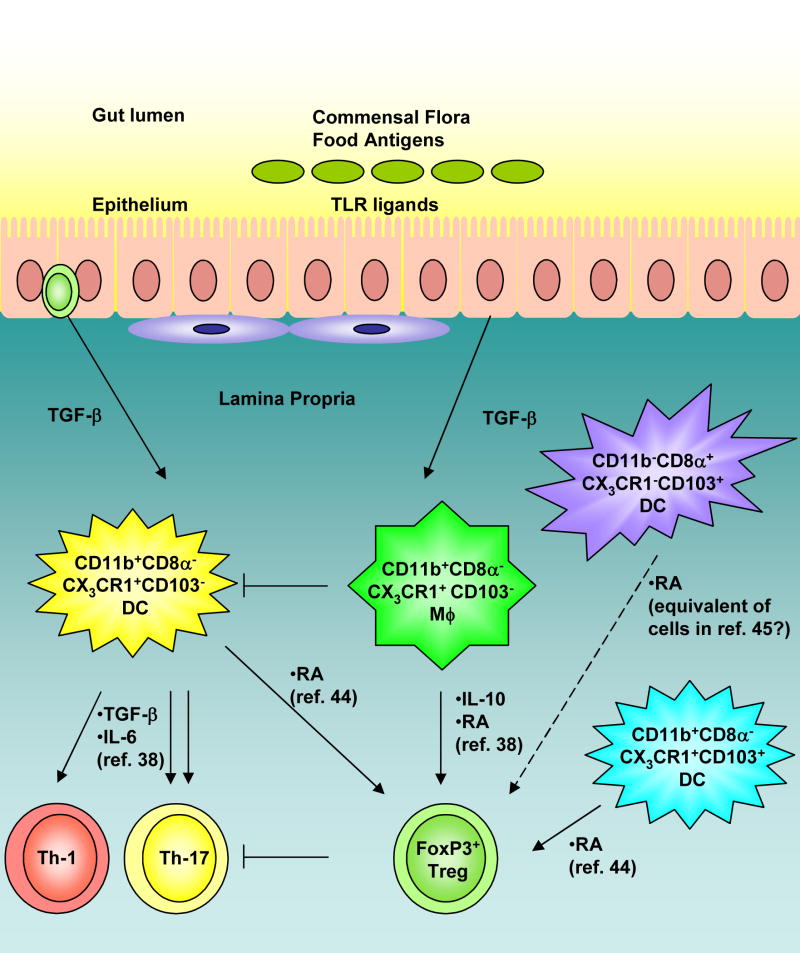

Figure 1. Crosstalk between subsets of antigen presenting cells in the lamina propria of the intestine.

Recent reports (refs. 38, 44, 45) show the existence of multiple subsets of antigen presenting cells in this microenvironment. Our recent work (ref. 38) describes the role of a unique subset of CD11b+ macrophages that promotes the differentiation of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells via secretion of IL-10 and retinoic acid (RA). These cells can also abrogate the induction of Th17 responses induced by TGF-β secreting CD11b+ DCs. In contrast, Belkaid et al. (ref. 44) have demonstrated that CD11b+CD103+ and CD11b+CD103− DCs in the LP may also promote the generation of regulatory T cells via RA. In addition, Powrie et al. (ref. 45) have reported that CD103+ DC in the mesenteric lymph nodes can also induce regulatory T cells via RA. The relationships between the DCs subsets described by these three groups and others are at present poorly understood. Nevertheless these findings highlight mechanisms of crosstalk between DCs and macrophages in the intestine.

Another example of DC-DC collaboration was demonstrated by Kuwajima et al (58) who showed that CpG-treated IL-15-deficient mice produced little IL-12 and succumbed to L. monocytogenes. CpG-stimulated conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) were the main producers of both IL-15 and IL-12, but cDCs did not produce IL-12 in the absence of plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs). The cDC-derived IL-15 induced CD40 expression by cDCs. Interaction between CD40 on cDCs and CD40 ligand on pDCs led to IL-12 production by cDCs. Thus, IL-15-dependent crosstalk between cDCs and pDCs is essential for CpG-induced immune activation.

Yet another example of DC-DC cooperation appears to occur during priming of CD8+ T cell responses. As stated above, CD8α+ DCs are very efficient at cross-presentation of exogenous antigens to CD8+ T cells (23, 24). Since CD8α+ DCs are present in the T cell rich areas of the lymph nodes, it is still not clear how they access antigens that might have been injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly. One possibility is antigen at these sites are carried via lymph within hours of even minutes of injection (59). However, a different although not mutually exclusive, possibility is that DCs at the site of injection ferry the antigen to the draining lymph node, where they then transfer the antigen, via some unknown mechanism, to resident DCs (60). Evidence for this comes from studies which show that although the migration of Langerhans cells or dermal DC from the skin to the lymph nodes are required for immunity, that such cells themselves do not seem capable of presenting antigen to CD8+ T cells; rather, resident CD8α+ DCs seem to be the most efficient at presenting to CD8+ T cells (61, 62).

Finally, our recent work suggests a dynamic interplay between DCs and neighboring macrophages in the lamina propria (Figure 1; 38). Interestingly, the macrophages in this environment constitutively produce IL-10 and retinoic acid, are hyporesponsive to TLR stimulation, and in conjunction with TGF-β induce T regulatory cells. In contrast, DCs which are in close proximity to the macrophages, the same microenvironment, induce potent Th17 cells (38). Importantly the macrophages appear to exert a dominant effect in suppressing the induction of Th17 cells by the DCs. It should be noted that a LP DCs were recently shown to induce T regulatory responses (44); the reasons for the discrepancy between our findings and those of Belkaid and colleagues (44) are not clear, but may lie with the nature of the DC subset being studied. This discrepancy notwithstanding, this is an example in which two distinct subsets of antigen presenting cells in the identical microenvironment, induce very different T helper responses, and cross regulate each other (Figure 1).

Therefore, these recent observations highlight a hitherto unappreciated level of complexity in the DC system. These observations raise some important questions. For example, how do such cross talks shape the strength, quality and longevity of innate and adaptive immune responses, and immunological memory? To what extent can insights regarding transfer of antigens from skin DCs to lymph node DCs obtained from studying a single pathogen or antigen be extrapolated to other pathogens and antigens? Do different adjuvants stimulate crosstalk between different sets of DCs? Should vaccines target more than one DC subset in order to stimulate the right dialogue, and thus the right type of immune response? Future studies using elegant strategies, such as the conditional knockout of various DC subsets, together with live imaging techniques, should yield exciting answers to these questions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Coffman RL. Origins of the T(H)1-T(H)2 model: a personal perspective. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:539–7541. doi: 10.1038/ni0606-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner SL. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007;129:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettelli E, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Th17: the third member of the effector T cell trilogy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007 Aug 31; doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belkaid Y. Regulatory T cells and infection: a dangerous necessity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 Oct 19; doi: 10.1038/nri2189. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawrylowicz CM, O’Garra A. Potential role of interleukin-10-secreting regulatory T cells in allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:271–283. doi: 10.1038/nri1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinman RM, Hemmi H. Dendritic cells: translating innate to adaptive immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:17–58. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueno H, Klechevsky E, Morita R, Aspord C, Cao T, Matsui T, Di Pucchio T, Connolly J, Fay JW, Pascual V, Palucka AK, Banchereau J. Dendritic cell subsets in health and disease. Immunol Rev. 2007;219:118–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady-state and inflammatory dendritic-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19–30. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulendran B. Modulating vaccine responses with dendritic cells and Toll-like receptors. Immunol Rev. 2004;199:227–250. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwaskai A, Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449:819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pulendran B, Palucka K, Banchereau J. Sensing Pathogens and Tuning Immune Responses. Science. 2001;293:253–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1062060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulendran B. Variegation of the immune response with dendritic cells and pathogen recognition receptors. J Immunol. 2005;174:2457–2465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Wicks I, Wu L, O’Keeffe M, Shortman K. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niess JH, Reinecker HC. Dendritic cells: the commanders-in-chief of mucosal immune defenses. Curr Opin Gastroentero. 2006;22:354–360. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000231807.03149.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson C, Kelsall BL. Phenotype and function of intestinal dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pulendran B, Lingappa J, Kennedy MK, Smith J, Teepe M, Rudensky A, Maliszewski CR, Maraskovsky E. Developmental pathways of dendritic cells in vivo: distinct function, phenotype, and localization of dendritic cell subsets in FLT3 ligand-treated mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:2222–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulendran B, Smith JL, Caspary G, Brasel K, Pettit D, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski CR. Distinct dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate the class of immune response in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1036–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maldonado-López R, De Smedt T, Michel P, Godfroid J, Pajak B, Heirman C, Thielemans K, Leo O, Urbain J, Moser M, et al. CD8alpha+ and CD8alpha− subclasses of dendritic cells direct the development of distinct T helper cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;189:587–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soares H, Waechter H, Glaichenhaus N, Mougneau E, Yagita H, Mizenina O, Dudziak D, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. A subset of dendritic cells induces CD4+ T cells to produce IFN-gamma by an IL-12-independent but CD70-dependent mechanism in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1095–106. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.den Haan JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(−) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pooley JL, Heath WR, Shortman K. Cutting edge: intravenous soluble antigen is presented to CD4 T cells by CD8− dendritic cells, but cross-presented to CD8 T cells by CD8+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5327–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinman RM, Turley S, Mellman I, Inaba K. The induction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have captured apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:411–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, Cheong C, Liu K, Lee HW, Park CG, et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.den Haan JM, Bevan MJ. Constitutive versus activation-dependent cross-presentation of immune complexes by CD8(+) and CD8(−) dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;196:817–827. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao W, Liu YJ. Innate immune functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu YJ. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:275–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai Y, et al. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yrlid U, Jenkins CD, MacPherson GG. Relationships between distinct blood monocyte subsets and migrating intestinal lymph dendritic cells in vivo under steady-state conditions. J Immunol. 2006;176:4155–4162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sunderkotter C, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–4417. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Freshly isolated Peyer’s patch, but not spleen, dendritic cells produce interleukin 10 and induce the differentiation of T helper type 2 cells. J Exp Med. 1999;190:229–239. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iwasaki A, Kelsall BL. Unique functions of CD11b+, CD8 alpha+, and double-negative Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:4884–4890. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contractor N, Louten J, Kim L, Biron CA, Kelsall BL. Cutting edge: Peyer’s patch plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce low levels of type I interferons: possible role for IL-10, TGFbeta, and prostaglandin E2 in conditioning a unique mucosal pDC phenotype. J Immunol. 2007;179:2690–2694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denning TL, Wang YC, Patel SR, Williams IR, Pulendran B. Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1086–1094. doi: 10.1038/ni1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chirdo FG, Millington OR, Beacock-Sharp H, Mowat AM. Immunomodulatory dendritic cells in intestinal lamina propria. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1831–1840. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rescigno M, Urbano M, Valzasina B, Francolini M, Rotta G, Bonasio R, Granucci F, Kraehenbuhl JP, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cells express tight junction proteins and penetrate gut epithelial monolayers to sample bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:361–367. doi: 10.1038/86373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA, Vyas JM, Boes M, Ploegh HL, Fox JG, Littman DR, Reinecker HC. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science. 2005;307:254–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Pabst O, Palmqvist C, Marquez G, Forster R, Agace WW. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1063–1073. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Annacker O, Coombes JL, Malmstrom V, Uhlig HH, Bourne T, Johansson-Lindbom B, Agace WW, Parker CM, Powrie F. Essential role for CD103 in the T cell-mediated regulation of experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1051–1061. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.**.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, Belkaid Y. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.**.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.**Benson MJ, Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle R. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enganced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.**.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovaskaya O, Scot I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. References 44 and 45 papers demonstrate that DCs in the LP (44) and MLN (44) induce T regulatory responses, via a mechanism involving retinoic acid. References 46 and 47 highlight a potent role for RA in the induction of T regulatory responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. T-cell priming by type-1 and type-2 polarized dendritic cells: the concept of a third signal. Immunol Today. 2000;12:561–567. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spörri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory mediators are insufficient for full dendritic cell activation and promote expansion of CD4+ T cell populations lacking helper function. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:163–170. doi: 10.1038/ni1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwissa M, Kasturi SP, Pulendran B. The science of adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:673–684. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Svensson M, Maroof A, Ato M, Kaye PM. Stromal cells direct local differentiation of regulatory dendritic cells. Immunity. 2004;21:805–816. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang M, Tang H, Guo Z, An H, Zhu X, Song W, Guo J, Huang X, Chen T, Wang J, Cao X. Splenic stroma drives mature dendritic cells to differentiate into regulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1124–1133. doi: 10.1038/ni1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.*.Ito T, Wang YH, Duramad O, Hori T, Delespesse GJ, Watanabe N, Qin FX, Yao Z, Cao W, Liu YJ. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1213–1223. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051135. This paper highlights a mechanism by which TSLP conditioned DCs drive Th2 responses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.**.Rimoldi M, Chieppa M, Salucci V, Avogadri F, Sonzogni A, Sampietro GM, Nespoli A, Viale G, Allavena P, Rescigno M. Intestinal immune homeostasis is regulated by the crosstalk between epithelial cells and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:507–514. doi: 10.1038/ni1192. This paper describes a fundamental mechanism by which stromal cells in the intestine condition DCs to drive Th2 responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou B, Comeau MR, De Smedt T, Liggitt HD, Dahl ME, Lewis DB, Gyarmati D, Aye T, Campbell DJ, Ziegler SF. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin as a key initiator of allergic airway inflammation in mice. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/ni1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.**.Watanabe N, Wang YH, Lee HK, Ito T, Wang YH, Cao W, Liu YJ. Hassall’s corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature. 2005;436:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature03886. This paper highlights a fundamental mechanism involving TSLP, by which Hassall’s corpuscles drive T regulatory cells in the thymus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.**.Yoneyama H, Matsuno K, Toda E, Nishiwaki T, Matsuo N, Nakano A, Narumi S, Lu B, Gerard C, Ishikawa S, Matsushima K. Plasmacytoid DCs help lymph node DCs to induce anti-HSV CTLs. J Exp Med. 2005;202:425–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.**.Kuwajima S, Sato T, Ishida K, Tada H, Tezuka H, Ohteki T. Interleukin 15-dependent crosstalk between conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cells is essential for CpG-induced immune activation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:740–746. doi: 10.1038/ni1348. References 57 and 58 provide the first description of mechanisms of cooperation between DC subsets. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Itano AA, McSorley SJ, Reinhardt RL, Ehst BD, Ingulli E, Rudensky AY, Jenkins MK. Distinct dendritic cell populations sequentially present antigen to CD4 T cells and stimulate different aspects of cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 2003;1:47–57. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carbone FR, Belz GT, Heath WR. Transfer of antigen between migrating and lymph node resident DCs in peripheral tolerance and immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:655–658. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Allan RS, Smith CM, Belz GT, van Lint AL, Wakim LM, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Epidermal viral immunity induced by CD8alpha+ dendritic cells but not by Langerhans cells. Science. 2003;301:1925–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.1087576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R, Iwasaki A. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of Herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:513–520. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]